Digital solutions for people and nature

Protecting forest elephants, predicting harvests or recognising pathogens: these German-African projects show how all these projects and more besides work using artificial intelligence.

Artificial intelligence opens up new opportunities when it comes to tackling global challenges – in all kinds of areas ranging from healthcare to animal welfare. German-African cooperation is creating innovative approaches that benefit people and nature in equal measure. Whether identifying pathogens within minutes, protecting forest elephants or predicting the harvest – these projects show how AI can create solutions for a sustainable future.

Better protection for forest elephants

For AI to be used, the algorithm first has to undergo a learning process. This is currently happening in a project being run by the environmental protection organisation WWF Germany and the IT company IBM. In future, AI software will not only count forest elephants that have previously been recorded by a camera in the rainforest. It will also be able to identify the elephants individually. “This is completely new,” says Thomas Breuer, Central Africa Officer at WWF Germany and Forest Elephant Coordinator. “In order for the algorithm to learn to identify unknown animals, you first need animals that have already been identified,” he says. The idea is that counting the animals will help ensure they enjoy better protection. “The researchers on site know many of the elephants as individuals. This enables us to tell the algorithm which elephant is which.” The AI then needs to be trained and tested. “It will probably be a few years before we have solar-powered camera traps with an integrated algorithm and real-time transmission in the rainforest,” says Breuer. But the development of AI is progressing quickly – even though a lot of work is needed at the beginning.

Rapid identification of pathogens

The University of Münster has developed a quick and inexpensive method for detecting pathogens. All the researchers need is a computer, a microscope with a camera and software that can distinguish between different pathogens. “The great thing about our approach is that we carry out simple microscopic staining, which is then interpreted using AI,” says Professor Frieder Schaumburg, Director at the Institute of Medical Microbiology. “The identification process takes about 15 minutes. The cost of the materials will be a matter of cents.” The new method is soon to be trialled at two of the university’s African partner hospitals: Masanga Hospital in Sierra Leone and Hôpital Albert Schweitzer in Gabon.

Chatbots in the local language

If a lot of people are to benefit from AI, the technology has to be able to speak their language. To make this possible, the initiative FAIR Forward was launched in 2019 by the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). “Up until now there’s hardly been any AI-processed language data available for African languages in particular,” says Jonas Gramse, Project Manager at FAIR Forward. “But we need this data so as to be able to develop things like translation tools and chatbots for local languages.” In Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda, FAIR Forward helped set up publicly available databases in the languages Kiswahili, Kinyarwanda and Luganda. In Rwanda, a chatbot was developed to inform people about COVID-19 in the local language Kinyarwanda. “FAIR Forward promotes open, non-discriminatory access and the ethical use of AI,” says Gramse of the initiative, which also advises on human rights and data privacy issues.

AI in agriculture

In addition to languages, FAIR Forward also focusses on geodata for AI in agriculture. “This enables farmers to predict their harvest or detect pests,” says Gramse. FAIR Forward supports companies and organisations in Africa and Asia through the Open Source AI Business Mentorship Programme, for example. One participant was Kenya’s Local Development Research Institute, which offers farmers early warning systems. And then there’s the company M-Omulimisa in Uganda, which uses AI-based yield forecasts to help farmers obtain loans more easily.

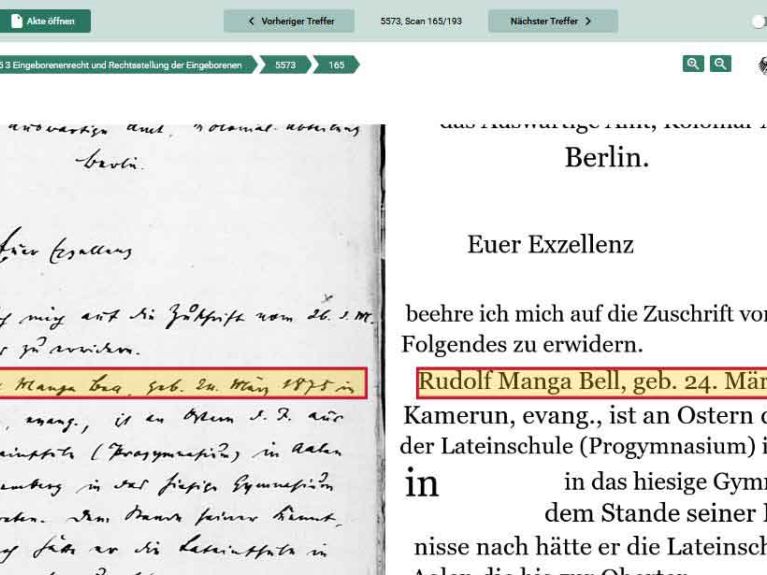

Researching colonial history with AI

Deciphering unfamiliar manuscripts can be difficult – especially if the text is written in an old script. The German Federal Archives have used AI to develop a programme for manuscript recognition with the aim of helping to undertake a reappraisal of German colonial crimes. Researchers will now find it easier to read and search the approximately 10,000 files of the Imperial Colonial Office, which contain numerous texts written in Sütterlin script. Sütterlin is a German script that was introduced at the beginning of the 20th century, but it is hardly used any more. In two years’ time the documents will no longer just be available on site, but will be able to be viewed by users online as well.

Networked science

The Responsible AI Network Africa (RAIN Africa) is a network for scientists working on AI that was set up in 2020. The project emerged from a partnership between the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Ghana and the Institute for Ethics in Artificial Intelligence at the Technical University of Munich (TUM). Researchers from several African countries and Germany share ideas on the promotion of AI in areas such as health or education, for example, as well as discussing its social and ethical implications. "A interesting component of this international network is the inherent need to think about how context and culture may shift these discussions or approaches, as we are often only confronting a more European approach to these questions here at home," says Caitlin Corrigan of TUM.