Erich Kästner: a great children’s book author – and much more besides

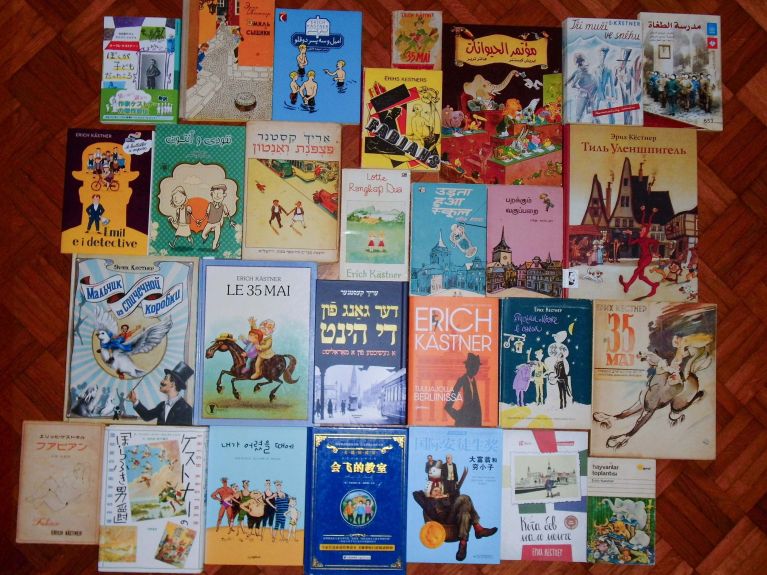

His children’s books have been translated into more than 70 languages and continue to sell millions of copies to this day. Erich Kästner didn’t just write for young readers, however.

The train rattles along towards the capital, Emil has fallen asleep and is dreaming bizarre things. When he wakes up, his money has disappeared. He suspects the mysterious man in the hat who was seated in the compartment with him previously – and a wild chase through Berlin starts. Emil finds companions, and a gang of clever city kids challenge the adult world to ensure justice is upheld.

“Emil and the Detectives” was Erich Kästner’s first children’s book: published in 1929, it made him an instant star of the German – and international – literary scene. An exciting story set in the big city, it is still highly popular the world over and has been made into a film several times. Further children’s books followed – all of them timeless classics: “Pünktchen und Anton” (“Dot and Anton”, 1931), “Das fliegende Klassenzimmer” (“The flying classroom”, 1933) and “Das doppelte Lottchen” ( “Lisa and Lottie”, 1949).

Romance writer and pacifist

With 2024 marking the 125th anniversary of his birth and the 50th anniversary of his death, Kästner remains famous above all for his stories of courageous, inventive and adventurous children. He is not just remembered as a leading children's author, however, but also as a writer of extremely sophisticated literature. Not published in unabbreviated form until long after his death, in 2013, his novel “Der Gang vor die Hunde” (“Going to the Dogs”) is considered a masterpiece. It is the story of an unemployed German scholar who wanders through the wild Berlin of the late 1920s. The book was published in 1931 under the title “Fabian”, though the publisher removed erotic passages at the time. Kästner was also a lyricist, a witty chronicler and a critical observer of German society. Last but not least, he was a staunch pacifist who stood up for peace and democracy after the horrors of National Socialism.

A would-be teacher

Born in Dresden in 1899, Erich Kästner grew up as an only child in humble circumstances. His father worked in a suitcase factory, while his mentally unstable mother – with whom he had a close relationship until her death in 1951 – was employed as a maid, a home worker and a hairdresser. In 1913, Kästner went to a boarding school that trained future teachers. It was at this time that he began to publish his first poems in the school newspaper. He dropped out of his training as a primary school teacher shortly before it ended. Kästner later wrote about the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 in his autobiography: “The world war began and my childhood was over.” He was called up for military service in 1917. The unforgiving harshness of being a soldier and the horrors of war triggered in him a deep aversion to militarism of any kind.

Career as a “utilitarian lyricist”

In 1919 Kästner began studying history, philosophy, German literature and theatre studies at the University of Leipzig, obtaining his doctorate in 1925. While still a student he started working as a journalist and became sought-after in the years that followed for the theatre critiques, reviews, reports, commentaries and satires that he wrote for various daily newspapers. He was now living in Berlin, the vibrant metropolis of the golden 1920s. An urban poet, Kästner became well-known for the bitter irony of his verse. Kästner himself described these works as “utilitarian poetry” – poems for everyday life. And it is true to say that some of his aphorisms did actually find their way into the everyday language of his fellow countrymen – such as the saying “Es gibt nichts Gutes, außer man tut es” (“There is nothing good unless you do it”), an expression that is still commonly used in German today.

Book burning and publication ban

His popularity as an author and the great success of his children’s books were of little use to Kästner after the National Socialists came to power, however. Quite the opposite, in fact. His name quickly appeared on a list of banned writers. While many other artists and critical minds emigrated, Kästner remained in Germany – despite being arrested twice by the Gestapo. He was even present when the Nazis threw his works into the flames at the book burning on Berlin’s Opernplatz in May 1933, under the supervision of Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. He initially believed the nightmare would soon be over. What is more, he regarded himself as a contemporary witness and was keen to record what was happening in Germany. He then published several books abroad, including the very successful novel “Drei Männer im Schnee” (“Three Men in the Snow”) in 1934. Despite being banned in Germany, he continued to write under pseudonyms, including, surprisingly, the screenplay for the feature film “Münchhausen”, which was sponsored by Goebbels. When his involvement in this film came to light shortly before the premiere in 1943, Adolf Hitler is said to have been enraged. The consequence for Kästner was a definitive ban on any further writing activity.

Literary all-rounder and PEN President

After the end of the Second World War, Kästner moved to Munich, where he lived until his death on 29 July 1974. As a literary all-rounder, he was once again highly productive, writing effortlessly in a direct, clear-cut style. Among other things, he worked as the head of newspaper feature pages, editor of the children’s and youth magazine Pinguin, and as an author for cabaret theatre, radio and film. From 1951 to 1962 he was President of the German PEN Centre. Kästner remained true to his anti-militarism throughout his life, and was actively involved in the peace movement, often speaking words of warning. Erich Kästner’s work is still popular around the world today: with their light, cheerful touch and at times moralist tone, Emil’s adventures in Berlin are as timeless as Kästner’s adult literature and his verse.