Networking the world

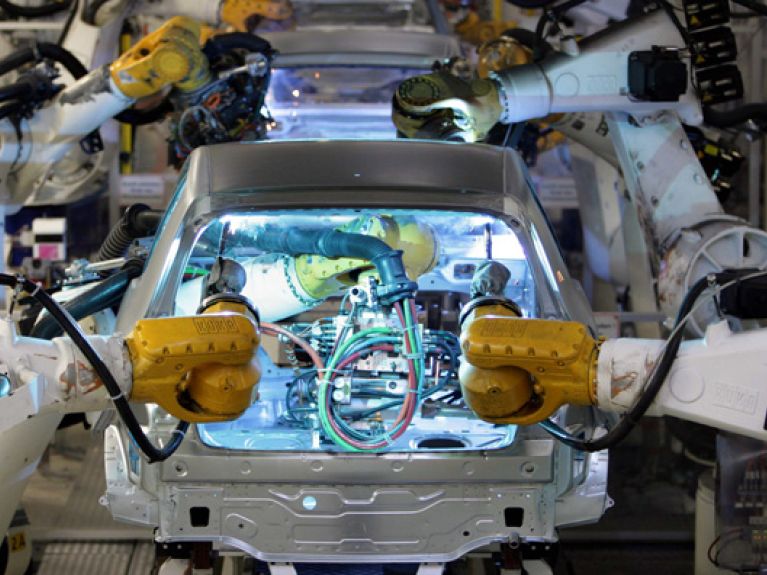

Machines are learning to talk, products are becoming smarter – so will people soon be superfluous? What are the consequences of digitization for industry?

Industry 4.0 is coming. We are experiencing the fourth industrial revolution – after the steam engine (first power loom 1784), mass production (first assembly line 1870) and electronics (first programmable logic controller 1969). Like the other three revolutions, the fourth also promises greater efficiency and higher productivity. Yet Industry 4.0 does not involve a new technology that was previously completely unknown. “It is the industrial application of production engineering technologies that have been used in consumer goods for a long time,” says Dieter Wegener, Vice-President Advanced Technologies & Standards, Industry Sector, Siemens AG. Wegener is thinking here for example of the use of wireless connections, which have long been standard in the consumer sector. And yet he would not contradict his boss: “Manufacturing and production engineering have never changed as quickly and fundamentally as they are changing today,” says Siegfried Russwurm, CEO Industry Sector and Member of the Managing Board, Siemens AG.

So what is Industry 4.0? Two things are crucial here. The ultimate goal is for the products to communicate with the machines that make them. Today, a production system is automated to achieve a high throughput in a short time. The focus is on economies of scale, on producing large batches in the shortest time possible. This only requires individual control of each machine. In the future, however, the goal will be for the machine – a robot, assembly line or machining centre – not only to carry out the work process for which it was programmed, but also to independently recognize which work process it has to perform on a new component. To make this possible the component has to carry a “business card” in the form of an electronic chip, a wirelessly readable identifier or a readable bar code similar to the ones we see at the supermarket. The machine recognizes the card and knows what to do. All components will no longer be processed identically, as is the case in present-day mass production. In the future, each product will be made according to highly specific requirements. Theoretically, the objective is not increasingly large, but increasingly small batches – or in extreme cases, automated individualized production. However, if every machine recognizes what it has to do to a component, the same technology can be used by components to find the right machine to be processed by. In other words, it can autonomously use spare capacity and does not have to follow a previously fixed production schedule.

Production in factories will become more efficient. However, this close and direct link between product and production only functions if there is duality. This means there has to be a virtual copy of every real object. Every product and every machine has to be recorded in digital form so that it can later communicate with other machines or components. They can both only communicate on the virtual level.

It will take decades for the fourth industrial revolution to spread to the far corners of the world

So far, the Internet has not even entered the game. “Industry 4.0 also works without the Internet,” says Siemens expert Wegener. But it functions even better – and above all over greater distances – with the Internet, because the Internet combines the possibilities of communication within the factory with communication with other factories, suppliers and customers. This leads to a market for capacity: in other words, a product autonomously looks for a processing location or the next workshop on the Internet. This is possible because the product carries with it its own increasingly long CV in the form of a chip with all the relevant data. That enables us to determine at any time who designed the product, where it was made, when and how any maintenance was carried out, what safety standards it meets, what electronic interfaces it has, and much more.

However, it will take a while before we reach that stage. Earlier technological revolutions took a long time to become fully established. Likewise, the fourth industrial revolution is likely to take decades rather than years to prevail in all corners of the globe. But this process has already started. Looking back, the beginnings will probably be dated around 2010 to 2013. The initial steps were taken in industrial automation – above all, therefore, in mechanical engineering and electrotechnology. Germany has been a leader in both these fields for a large number of years. Many experts therefore believe that the universal introduction of Industry 4.0 will lead to a major boom in orders, especially for German manufacturers of machinery and electrical systems such as Siemens, ABB and Trumpf, but also medium-sized manufacturers like Phoenix Contact, Harting or Weidmüller. More than 70% of the business representatives and university teachers surveyed by the Association for Electrical, Electronic & Information Technologies (VDE) believe that Industry 4.0 will increase Germany’s competitive edge and strengthen its economic position.

This represents a great opportunity to bring production back to Europe – also in electronics, a sector in which consumer products are almost exclusively in the hands of American manufacturers. Here, too, German manufacturers have a lot of experience, especially in production control and other areas of technical software. Industrial associations have already responded to the need for cross-sectoral cooperation: Industry 4.0 is being driven forward by the VDMA in mechanical engineering, the ZVEI in electrical engineering and Bitkom in information and communications technology.

Machines must not only learn to speak, they must also learn to speak the same language

Industry 4.0 is technically fascinating and sophisticated, but there are still many challenges to overcome. One major problem is data security. Two kinds of security are meant here. First, the data you collect must be secure in the sense of reliable. Second, it must be secure in terms of being protected against theft or damage from outside (hacker attacks, spying). Another difficulty is the lack of standardization. Machines must not only learn to speak, they must also to learn to speak the same language. In other words, interfaces need to be defined. This requires global standards (ISO standards). Again, Germany is in a leading position internationally with its standards organizations.

The new form of manufacturing will also change the world of work. Even fewer people will be employed in production, but there will be greater demand for staff with software and programming skills. Engineers with a purely mechanical orientation will disappear, while computer scientists will need greater knowledge of engineering. Wegener at Siemens is convinced that people will become more important in the new production world. They will perform less physical work and be more in demand in the creative process, as well as in planning, control and supervision. One important task will involve evaluating the abundance of available data to facilitate decision-making and simplifying structures. The goal is to be able to respond to global fluctuations in sales and to individual customer preferences by making production more versatile. It is likely to take decades rather than years before this is implemented everywhere.

Networking will cause a second, additional revolution. There will be a counterpart to Industry 4.0 on the consumer and customer side. Products will gradually become increasingly connected and communicate with each other. This will begin with intelligent household services and certainly not end with cars being constantly monitored by their manufacturers. But that’s another topic, even if many observers expect networking to make faster progress in that area than in production. ▪