40 years of German autumn

How the terror of the Red Army faction dominated the Federal Republic in 1977.

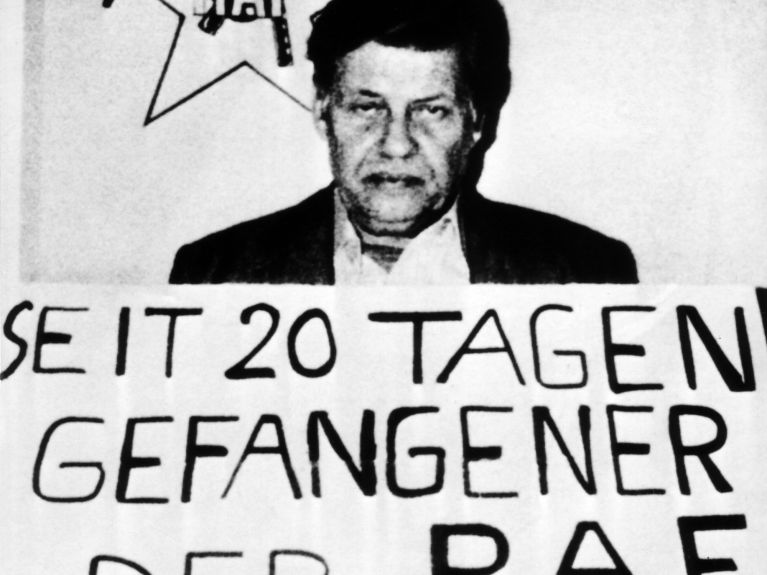

The photograph of the abducted and imprisoned German employers’ leader Hanns Martin Schleyer in front of the emblem of the Red Army Faction (RAF) – five-pointed star and submachine gun – is etched into Germany’s collective memory. The events of two months in the autumn of 1977 seemed to rapidly accelerate towards a catastrophe that threatened to pull the Federal Republic apart: Schleyer’s bloody abduction, then the hijacking of a Lufthansa airliner, its liberation and the death of three imprisoned RAF leaders in Stammheim Prison. With the three deaths in Stammheim, however, the apex of RAF terror had passed, even if the self-appointed, self-important Red Army Faction was able to execute a second wave of no less terrible attacks a few years later.

The state was unprepared

Then, during the months of September and October 1977, the Federal Republic indeed stood at the abyss. The state was unprepared for such a general attack of the kind executed by the RAF with its perfidious strategy of murders and hostage-takings. The sympathy that the RAF could at least initially rely on among members of the left-wing intelligentsia and even among broad sections of left-liberal voters resulted in a thoroughly defensive stance on the part of state and politics. The potent accusation of fascism always threatened all measures the politicians wished to take.

The seeds had been planted long before

All this culminated in the German Autumn, as it soon become known. However, autumn 1977 did not arise as swiftly as the events that characterised it. The first shoots appeared long before in the student protests of the late 1960s, in the demonstrations against the Vietnam War and above all in the rejection of the notorious emergency laws of May 1968 that a large section of the public regarded as the return to an authoritarian, if not even worse, state.

In other words, the ground on which the paranoia about a police state could flourish had already been prepared. Certainly, previously sympathetic intellectuals also turned away from the RAF and their propagandists after the first acts of terror. However, the avalanche had already been set in motion. By its nature, violence tends to escalate. The events of autumn 1977 forced an unprecedented confrontation. Helmut Schmidt’s Federal Government, including all the political forces of the Bundestag, accepted and overcame it, admittedly after the successful liberation of the hijacked airliner on 18 October in faraway Mogadishu. Subsequently people were prepared to judge leniently the de facto emergency situation that a “crisis committee” not envisaged under the constitution governed for one-and-a-half months.

Democracy grew as a result

Something else was decisive here: the fact that the society of the Federal Republic did not at all, not in the slightest, allow itself to be radicalised or swept into making ill-considered responses. “Bonn is not Weimar” was a dictum of the early Federal Republic, and here it became an empirical reality. The RAF and their kindred spirits mistakenly believed that, in keeping with Mao’s saying, they could “move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea”. The opposite was the case. These criminals – however political they may have presented themselves – received no support. The society of post-war Germany proved stable. The democracy of the Federal Republic, then less than 30 years old and sheltered within the Western alliance, passed its most difficult test. It grew as a result.

Author Bernhard Schulz works as editor of the culture section of Tagesspiegel, Berlin.