The Vormärz and Paulskirche parliamentary movement

Farewell to the German question – Looking back at the long journey West: 1830-1848 The Vormärz and Paulskirche parliamentary movement.

For the Germans there were always two sides to the German Question: that of territory and that of constitution, or to be more precise, the question of the relationship between unity and freedom. At the heart of the territorial question was the problem of a “larger Germany” or “smaller Germany”. If it were possible to replace the Holy Roman Empire with a German national state, would it have to include German-speaking Austria or was a solution to the German Question possible without these territories? The question of the constitution related primarily to the distribution of power between the people and the throne. In a united Germany who was to call the shots: the elected representatives of the Germans or the princes respectively their most powerful choice?

Unity and freedom first emerged as issues in the wars of liberation against Napoleon. The French Emperor was beaten but the removal of the foreign rulers brought the Germans neither a united Germany nor liberal conditions in the states of the German Confederation that in 1815 replaced the Old Reich. Yet the call for unity and freedom could no longer be suppressed permanently. In the early 1830s it once again became louder, the French having won their struggle for a liberal constitutional monarchy in the July 1830 revolution. And although in Germany the old rulers were once again able to get their way, from now on the Liberals and Democrats no longer remained silent. Inspired by events in France in February, in March 1848 there was a revolution in Germany, too: Unity and freedom were once again what the forces that knew historical progress was on their side demanded.

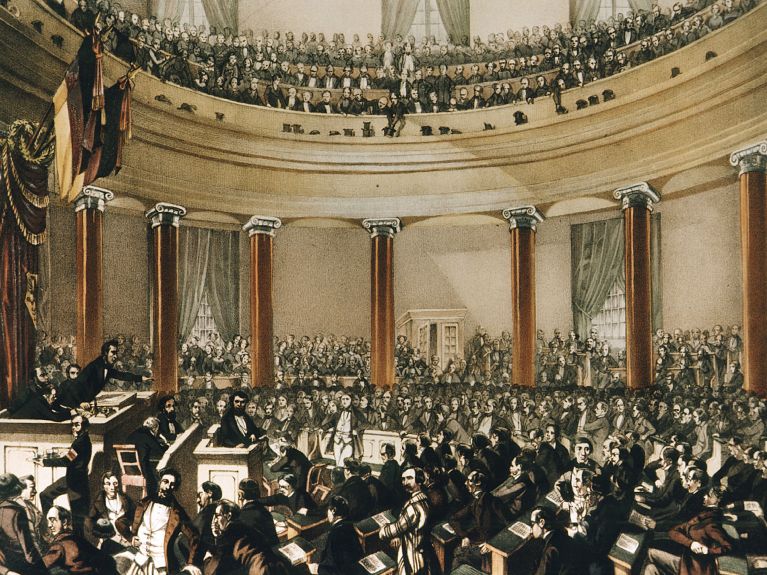

To make Germany both a nation and a constitutional state was a far more ambitious goal than that the French revolutionaries had set themselves in 1789, as their starting point was a nation state, which, albeit somewhat pre-modern, already existed and they therefore planned to place it on a completely new, civil basis. Anyone demanding unity and freedom for the Germans first of all needed to clarify what was actually to be part of Germany. In the first freely elected parliament, the National Assembly, which convened in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt/Main, the fact that a German nation state should include the German- speaking part of the Habsburg monarchy was initially beyond dispute. It was only as of fall 1848 that a majority of the Deputies came to the conclusion that it was not within their power to break up the multi-nation state of Austria-Hungary. Accordingly, as a “large” German state that included Austria could not be established, all that remained possible was a “small” German national state without Austria, and as things stood that meant a Reich under a hereditary Prussian Emperor.

The German state which, according to the will of the National Assembly in Frankfurt/Main, would have been headed by Frederick William IV of Prussia, would have been a liberal constitutional state with a strong parliament that had the government under its control. As German Emperor, the King of Prussia, of the House of the Hohenzollern, would have had to forego the divine right of kings and succumb to being the executor of the superior will of the people. It was a notion that on April 28, 1849 the monarch finally rejected, effectively sealing the fate of the revolution, which had thus brought the Germans neither unity nor freedom. What remained among the bourgeois Liberals was a feeling of political failure: they had, or so it seemed retrospectively, chased down countless illusions in that “mad year” and the realities of power proved them wrong.

It was not by chance that a few years after the 1848 revolution, “Realpolitik” was to become a political catchword: The term’s international career began with a pamphlet entitled “The Principles of Realpolitik. Applied to Conditions in the German States”, which the Liberal journalist Ludwig August von Rochau brought out in 1853. The Paulskirche had in fact already pursued a policy of “Realpolitik” when it ignored the right of self-determination of other peoples (the Poles in the Prussian Grand Duchy of Posen, the Danes in North Schleswig, and the Italians in “Welsch Tyrol”) and decided to define the borders of the future German Reich in line with supposedly German national interests. As such, unity was for the first time given a higher standing than freedom. The freedom of other nations still had to play second fiddle to the goal of German unity.