Learning from the Bauhaus

The White City in Tel Aviv is part of German-Israeli history – and present: Germans and Israelis are working together on the conversion of the Max Liebling House.

When training as a cabinetmaker, Berlin-based Laura Reti did not concern herself much with the Bauhaus. All that changed with a workshop at the Max Liebling House in Tel Aviv: In the house, built in 1934 by Dov Karmi in the Bauhaus style, Reti is busy together with Israeli design students restoring two “Frankfurt Kitchens”. These are widely considered the prototype modern unit kitchen and were designed to make housework easier for the woman of the house. When restoring the original wooden parts, and they are all more than 80 years old, the trainees not only learned all about the traditional trades techniques. What really impressed Reti was how the fit-out was ingeniously designed down to the smallest details: “These buildings mark the start of a new era,” she says, full of admiration.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formWhite City of Tel Aviv – a World Cultural Heritage site

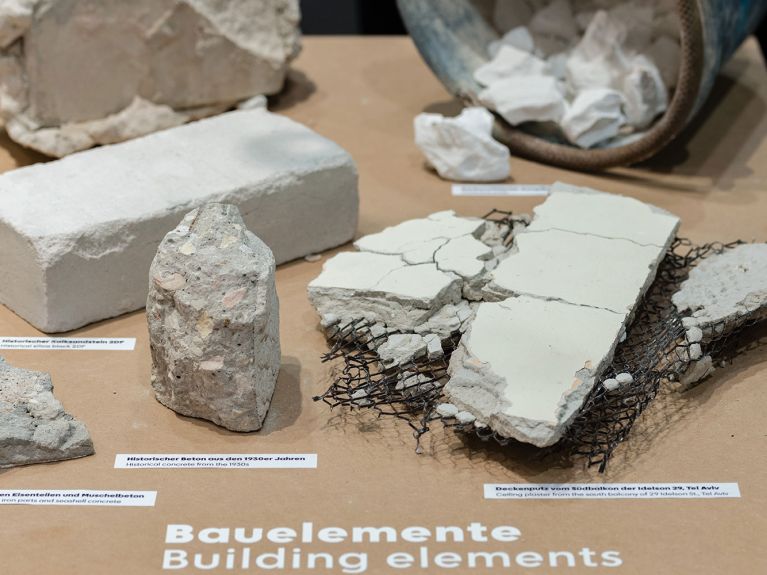

The Max Liebling House is one of the some 4,000 buildings that go to make up the White City of Tel Aviv. Its name derives from the way the white façades of the impressive ensemble shine in the sunlight and since 2003 the district has been included on the UNESCO World Cultural Heritage List. Jewish architects built the residential quarter with its flat roofs and rounded balconies, many of them having fled from Germany in the 1930s. They brought with them to Israel ideas influenced by the Bauhaus, adapted these to the climate of the metropolis on the Mediterranean coast and championed what is known in Tel Aviv as the “International Style” of Modernist architecture. The ensemble of original buildings in the Bauhaus style is unique the world over and part of German-Israeli history. However, that shared heritage is starting to flake: The plaster is starting to peel away from the once radiant façades and many of the buildings are in danger of collapsing.

German and Israeli preservationists have for many years joined forces in the “Network for the White City” to strive to protect the Bauhaus architecture and realise a centre for architecture and heritage preservation. The German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community (BMI) has provided funding of EUR 3 million through 2025 for the German-Israeli joint undertaking. With the White City Center scheduled to officially open in September 2019, the goal of developing joint strategies for the efficient and sustainable modernisation of the quarter in line with heritage requirements has come that bit closer. The Max Liebling House will be a venue for vibrant interaction, where experts will meet, tradespeople and restorers can take courses to improve their skills, and young people from Tel Aviv will gain a greater awareness of their native city’s cultural heritage.

Preserving the Bauhaus heritage

The red hard hats at the trade-fair booth where the White City Center presented its work in November 2018 at Leipzig’s “denkmal” trade fair programmatically symbolise its work. The wide-ranging campaign “open for renovation” offers guided tours, artistic activities and workshops, and defines the conversion work as an open process. Renovation of the Max Liebling House at 29 Idelson Street has itself morphed into a project that includes the general public: Groups of visitors stroll through the empty rooms and get an idea of the life of the former inhabitants; while young craftspeople are peeling paint off the plaster and modernising window frames, residents are busy tending the new organic garden – and revel in all the creative bustle going on around them.

“In Tel Aviv, ‘Bauhaus’ is more a slogan among estate agents used to boost their sales,” comments programme director Sharon Golan Yaron. She goes on to say that “this is why we primarily want to convey an emotional feel for the idea of the Bauhaus and thus promote an appreciation of this Modernist architecture.”

While the White City has long since been a magnet pulling tourists from all over the world, the inhabitants themselves have more of a pragmatic approach to the heritage buildings. Not only is there in part not enough knowhow to restore the houses in an appropriate way, but there is often not enough awareness of their cultural value, comments architect Sharon Golan Yaron. “Israelis tend to be more interested in practical matters; they adapt the houses to their lifestyles and their personal needs.” Storeys get added, or earthquake or missile protection introduced, original wooden windows replaced by modern double glazing, old terrazzo tiles simply taken to a dump.

Tough times for preservationists

In a city growing as rapidly as Tel Aviv, where there is a housing shortage and rents are skyrocketing, heritage preservationists have a tough time of it. Developers, architects and tenants are quite critical of the regulations to preserve the historical urban fabric. “Most of the houses are privately owned,” cautions State Secretary for Construction Gunther Adler during the trade fair in Leipzig. He’s a member of the Board of Trustees for the White City Center and has been supporting the joint undertaking from the outset. “It is important that we kindle interest and create incentives,” Adler emphasises. In the form of the Liebling House a prototype will emerge that shows owners a prime and vivid example of the knowhow required.

And this seems to be a successful strategy. “There was a time when windows simply got replaced; today, people often ask us how to do it,” relates Sharon Golan Yaron and points to a window made of wood at the rear wall of the trade-fair booth. “People can now see what is possible.” The reconstruction of a window from the Liebling House is part of the Israeli German Sustainable Building Education (IGSBE) project that architect Robert K. Huber launched with Israeli and German participants in Berlin and Tel Aviv.

The joint positive heritage of Modernist architecture is an invaluable asset.

On the basis of this best-practice project, trainees, students and interested specialists and amateurs spent three weeks restoring windows and balcony doors for the Max Liebling House – under the watchful eye of an experienced master cabinetmaker from Berufsförderungswerk des Bauindustrieverbandes Berlin-Brandenburg. “It was a real challenge to bring all the very different specialist requirements into line,” reports Robert Huber of Berlin’s “zukunftsgeraeusche” office. In Israel, there is no dual education programme like that in Germany and teaching tends to be more academic. Conversely, many craftspeople have not received formal instruction and have little expert knowledge. “It would be great going forward if we succeed in ensuring interaction between trainees and students,” Huber insists. The foundations have been laid: “Our goal was to launch, in the guise of the Teaching Building Site, a format that could be transposed onto other construction sites.”

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formTalk about the past openly

All the steps were laid down in a set of guidelines that can be used for subsequent crafts training sessions in the purpose-built workshop. The experiences gained have a far greater reach than simply expert knowledge. Huber says that “this form of collaboration offers marvellous opportunities for people to get to know each other and exchange opinions. The topic of migration is so present in this house that you invariably find yourself talking openly about it and the shared past in the course of the practical work – which ensures that the shared positive heritage of the Modernist architectural tradition forms an invaluable asset.”