Johannes Gutenberg – knowledge for the whole world

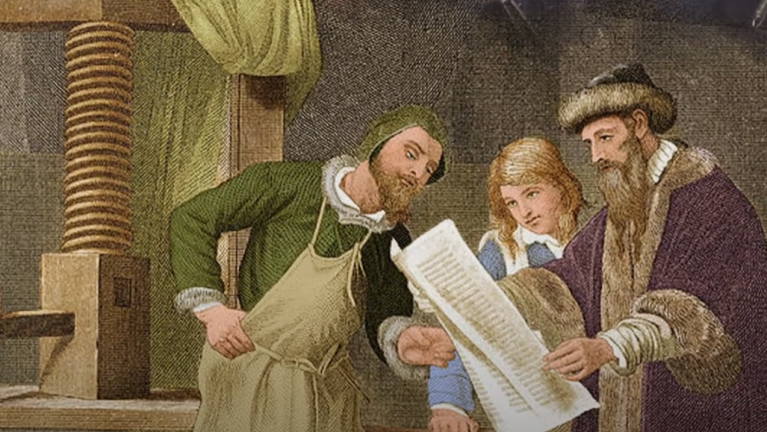

It was his invention of letterpress printing with movable type that enabled books to be produced rapidly and inexpensively.

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of classic letterpress printing brought about profound change in the western world. It wasn’t until books could be produced quickly and inexpensively that knowledge was able to spread rapidly. Letterpress printing was responsible for the huge impact of the Reformation, for example, as well as the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. It was Johannes Gutenberg who paved the way for everyone in Europe to be able to access information and education. The technique was in fact already long known in China – but this knowledge failed to spread to other countries.

The exact year of his birth is not known

It’s no easy task tracking down the genius who invented printing with individual letters. The facts we know about Johannes Gutenberg’s life are extremely sparse. Not even the exact year of his birth is known, though researchers have finally agreed that it was probably 1400.

Gutenberg came from a wealthy family in Mainz. His father worked in the cloth trade and also had income from property. While the elder son Friele was to take over the business, Johannes was destined for a career as a clergyman, doctor or lawyer. It is not known which school or university he attended, but as he would not have been able to print his books without a good knowledge of Latin and a basic familiarity with theology, it can be assumed that he enjoyed a thorough education.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formIn the 15th century, during the era of the Holy Roman Empire as Germany was then called, people were keen to set their ideas down on paper. Knowledge of technology and medicine was constantly growing, and there was a desire to share it. Those working in the trades and crafts saw the benefits of documenting contracts, orders and loans in writing. City and court administrations increasingly relied on well-educated civil servants. In short: there were more and more lawyers, theologians, philosophers and doctors – and they all needed books. At the time, these were copied by hand, which took a long time and was expensive. It was almost certainly early on that Gutenberg started thinking about how to speed up this process and make it cheaper.

Via Strasbourg back to Mainz

In 1434 Johannes Gutenberg moved to Strasbourg, where he worked as an entrepreneur, craftsman and inventor. He had inherited money and learned how to cut precious stones, and he also knew how to emboss and press metal. Since there are hardly any sources that reveal the details of his life, researchers repeatedly lose sight of the inventor. It was not until 1448 that he reappeared in Mainz, where he took out several loans to set up a printing press. He had evidently spent the previous years developing the equipment that was now to be used: a hand casting machine for producing metal letters, an angled hook and galley for setting the pages, and the printing press itself. Gutenberg was a perfectionist: he hired the very best craftsmen so that they could produce the machinery according to his plans and work with him on refining it.

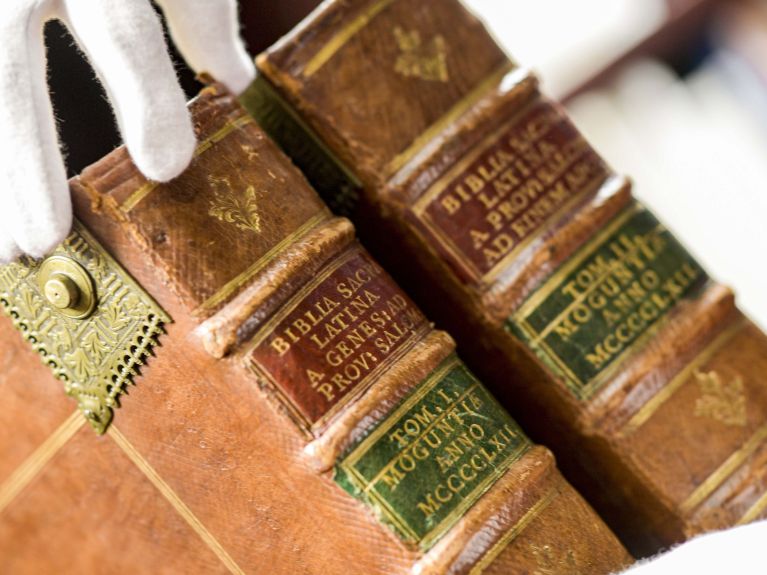

His first printed texts were no more than 30 pages long, consisting of calendars, letters of indulgence and a Latin grammar. It was a quick way to earn money. But Gutenberg then wanted to produce a book that dwarfed everything else, proving how groundbreaking and powerful his invention really was: he decided to print the Bible. This was not only the most famous and also the most valuable book, at least to Christians, it was also one of the most extensive pieces of writing in existence at the time. Gutenberg printed his Bible in two volumes, each of which had more than 600 pages. The format corresponded approximately to today’s A3.

He required vast quantities of type and supplies of parchment and paper, as he aimed to print no fewer than 180 copies. At times he had as many as 20 craftsmen working in parallel on three printing presses. The Gutenberg Bible is now considered a technical masterpiece and one of the most beautiful books in existence. 49 copies have survived to this day – 13 of which are kept in Germany, with additional copies in various European countries as well as in Japan and the USA.

Unlucky as a businessman

The ingenious inventor was unlucky as a businessman, however. His most important financial backer demanded that he repay the loan before the Bibles were finished. Gutenberg couldn’t pay him, so he had to leave him the workshop – complete with the almost finished Bibles. Gutenberg was able to keep one of the presses, however, and he continued to work as a printer, though only producing smaller works.

In 1465 the Archbishop of Mainz appointed Gutenberg a courtier, not only officially recognising his achievements but also providing him with financial support. Gutenberg was able to enjoy this for three more years before passing away on 3 February 1468, just before he reached the age of 70. He was buried in the Franciscan church in Mainz. Unfortunately the church has long since disappeared and it is no longer possible to find his grave.

___

Maren Gottschalk is the author of the biography Johannes Gutenberg: Mann des Jahrtausends.