Käthe Kollwitz – a dauntless woman and major artist

Her works are of timeless significance and exceptional artistic quality. Käthe Kollwitz campaigned against war and poverty and for the rights of women.

In a final letter written to her son Hans on 16 April 1945 in the final days of the Second World War, Käthe Kollwitz seemed disillusioned. “This war will follow me until the very end,” she wrote.Six days later, Germany’s most famous female artist was dead. She passed away alone in Moritzburg near Dresden, aged 77. With the Russian army approaching, it was impossible for her son, her sister or her granddaughters to be with her. The Second World War had robbed her of her health and any remaining hope. Her grandson served in the army and died in 1942. She had already lost her son Peter to the First World War. She responded to the trauma of this key event with moving artworks on the themes of death and grief. In this way, war really had dogged Kollwitz’ every step. War is a theme which is often associated with the artist.

Now we once again live in warlike times. Wars such as those in Ukraine and the Middle East are in the media every day. Perhaps that is why Käthe Kollwitz is attracting attention once again more than ten years after the last major exhibition of her work. A new exhibition entitled “Kollwitz” is running in Frankfurt am Main, presenting her work on paper, sculptures and early paintings. The Museum of Modern Art in New York is hosting the first major American display of Kollwitz’ work in 30 years. An exhibition is also planned in Copenhagen in Denmark.

Käthe Kollwitz was an artist, pacifist and feminist

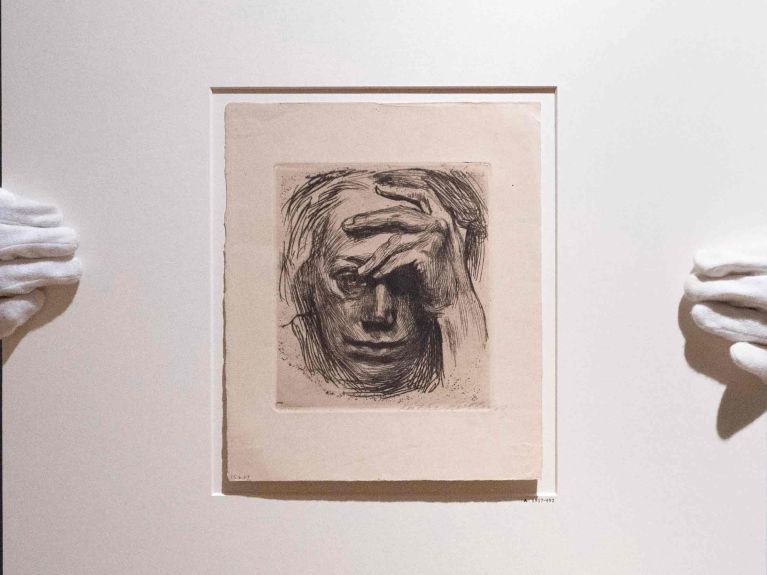

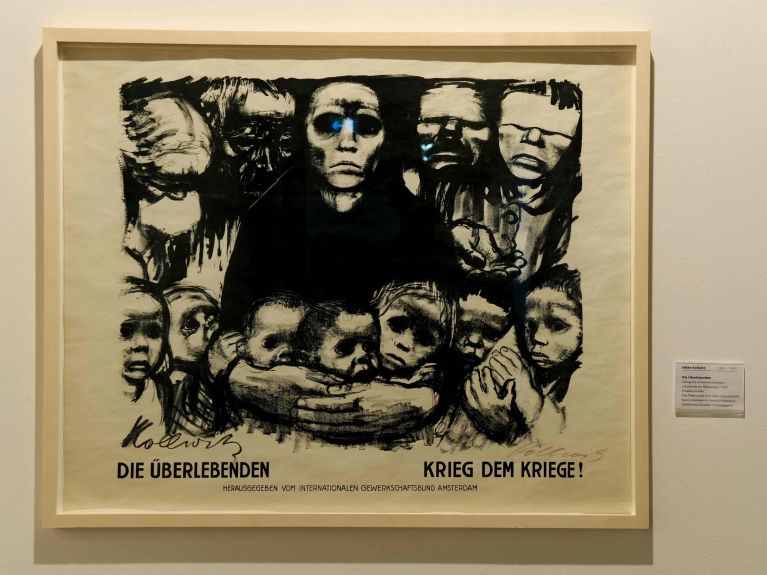

Her role as a pacifist and politically engaged artist is certainly a factor in this renewed interest. But Kollwitz was also a feminist and a strong and unconventional woman in general, which also makes her seem very modern. In addition to this, in her 55-year career, her work dealt with grief and death, poverty and work, love and motherhood. She herself described these themes as “primordial”. Her style was naturalistic, serious, and at times horrifyingly realistic or expressive. Although she created major sculptures such as the anti-war memorial “Grieving Parents”, the medium for the majority for her work was print or drawing.

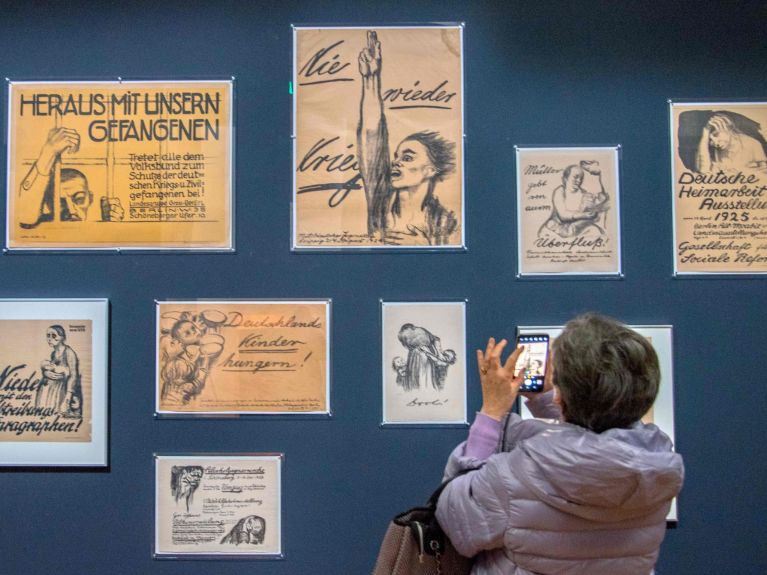

Her work “Never Again War” left its mark on generations

Where the circumstances demanded it, she did not shy away from striking messages and motifs. Famous around the world from placards held aloft at peace marches, her poster “Never Again War” from 1924 shows a young man raising his arm as he takes an oath. “I accept that my art has a purpose. I want to make a difference in this age, when people are so lost and helpless,” said Käthe Kollwitz in 1922. Yet you cannot help but immediately think of the age we live in today. Kollwitz achieved her artistic breakthrough with her cycle “A Weavers’ Revolt”, which she completed in 1897 and was inspired by Gerhart Hauptmann’s play “The Weavers”. However, when she presented the work at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, Kaiser Wilhelm II refused her a medal as she was a woman. But in this he did her a great service, as it made her famous well beyond Berlin.

I want to make a difference in this age, when people are so lost and helpless.

Yet Kollwitz’s well-deserved breakthrough was just as much due to the intensity and expressiveness with which she presented the suffering of the weavers in bleak black-and-white tones. She found success again with her cycle “Peasants’ War”, which she created between 1901 and 1908. These at times harrowing works – one of which depicts a victim of rape – she became the first woman and graphic artist to be awarded the Villa Romana Prize, which had been set up by Max Klinger. This itself was an honour for Kollwitz, who counted the symbolist artist Max Klinger alongside the impressionist Max Liebermann and the sculptor Ernst Barlach as her role-models.

Kollwitz’s career reached its apogee in 1919 when she became the first woman to be elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts in over a century. The same year she was made a professor, and her 60th birthday in 1927 was honoured with two exhibitions in Berlin alone. However, her career suffered a setback in the 1930s when she faced an indirect ban on exhibiting her work under the Nazis. Yet she continued to create major works. One was her small sculpture “Pietà (Mother and Dead Son)”, from 1937. This was the subject of a controversy when the Chancellor Helmut Kohl displayed an enlarged copy of the work in the Neue Wache in Berlin in 1993 as a memorial to the victims of war and tyranny. How, it was asked, was the Christian motif of the Pietà supposed to commemorate the Jews murdered in the Holocaust?

Which brings us to how postwar politicians have appropriated Kollwitz. For many years she was honoured in West Germany as a consoler and mother, while she was held up in East Germany as an anti-fascist and champion of the proletariat. In both East and West Germany, many schools, streets and squares came to be named after her. There has been a Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Cologne since 1985, and this was followed by another in Berlin in 1986, the city where she and her husband the doctor Karl Kollwitz lived for decades. Yet Kollwitz was born on 8 July 1867 in East Prussia in the city of Königsberg, now the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. The city’s fame now mainly rests on its connection with the famous philosopher Immanuel Kant, though in Käthe Kollwitz it has at least one equally famous daughter.