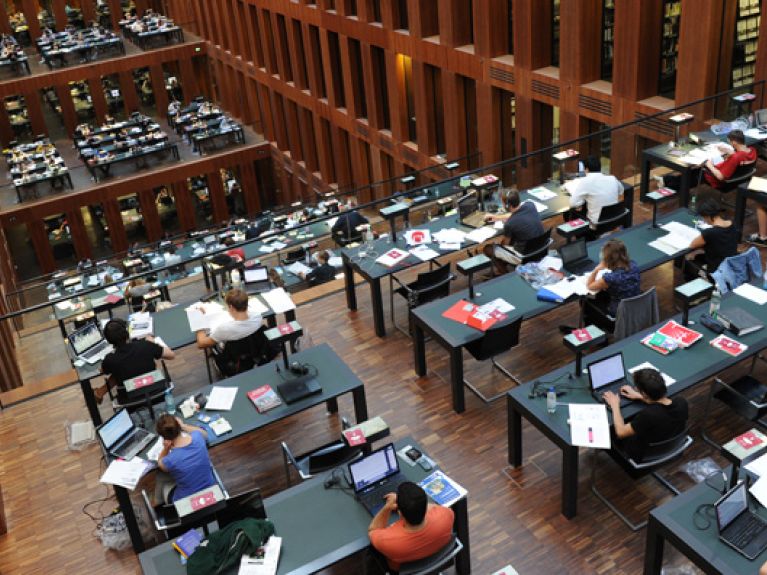

Centres of learning

Universities in the global knowledge society.

Universities in the global knowledge society

Since Wilhelm von Humboldt’s reforms – in other words, since the beginning of the 19th century – teaching in the humanities and the social sciences at universities in Germany has been characterized by instruction in seminars and colloquia. Teaching has thus been based on joint problem-oriented dialogue between teacher and student. The lecture as a form of knowledge transfer in which one person speaks and others write notes has played only a subordinate role alongside this. At school, according to Humboldt, the teacher serves the pupils; at university, on the other hand, professors and students work together in the service of science and scholarship. This was a revolutionary idea that resulted in German universities gaining worldwide recognition. What is left of this today?

The situation has changed a little since the introduction of Bachelor and Master degrees. The mere communication of knowledge – in other words, also the lecture – has become more important in the period leading up to the examinations for a Bachelor degree. In Master programmes, on the other hand, seminars and joint discussion continue to predominate. Overall, as a result of the Bologna Process, the harmonization of higher education qualifications in Europe, the number of students dropping out of higher education in Germany has declined significantly. The price for this is a certain reduction in the “loneliness and freedom” that Humboldt declared a prerequisite for science and scholarship. You can now really only exploit this freedom while studying for a Master. If you wish to study at a German university in order to gain real and deeper insights into the German research system, you will largely have to complete a Bachelor degree first. But where is the best place to do that?

The German university system is characterized by a fundamental paradox: its major weakness also gives rise to its strength. The reason for this paradox lies in Germany’s federal constitutional structure and the fact that university funding is a matter for the 16 Länder, the individual states. This even goes as far as a total ban on co-funding and means that Federal Government funds can only be allocated to universities through special temporary programmes. In rather simple terms, it can be said that universities in “rich” states are generally better equipped than those in their less well-off neighbours. Nevertheless, German higher education is less hierarchical than in other European countries. This has also not changed as a result of the so-called Excellence Initiative, which has provided additional funding for universities over recent years. Although the initiative has made a number of strong institutions considerably stronger, it cannot be said the universities that did not receive excellence status have become second class institutions. In fact, the German university system tends to be characterized by flat hierarchies.

It is still possible to observe the trinity that developed during the 19th century. “Student life” is strongest at universities that dominate the social character of a town. Cities like Heidelberg, Marburg and Tübingen are still typical, traditional student towns. Then there are universities that are located in big cities or state capitals and therefore have a certain “political visibility”. This is where the modernization of learning and curricula has progressed most as a rule. Finally, there are the universities that have a series of outstanding researchers, sometimes even Nobel Prize winners, among their staff, frequently in collaboration with Max Planck institutes or Leibniz Association centres, and have therefore accrued greater international prestige. This is where ideas of academic excellence are most developed.

The respective reputation of a centre of learning usually depends crucially on which of the three branches of scholarship you examine: the natural sciences, the social sciences or the humanities. Undoubtedly, the allocation of financial resources plays the main role in the promotion of excellence in the natural sciences, whereas in the humanities it is not uncommon for a single “great mind” to boost a university’s reputation and prestige. To simplify somewhat: while the natural sciences need large teams of researchers with lots of laboratories and equipment, the humanities require individuals with an intellectually stimulating environment and the time it takes to write books. The social sciences are somewhere in between. The Excellence Initiative has actually only been relevant to the “teams”, while the “great minds” have seldom been affected by it. The commotion caused by the entire “excellence operation” has probably often been more of a hindrance that a help to them. If their work has been affected, then it is less due to a lack of funds and more as a result of excessive teaching activity. Nevertheless, a great deal has improved here.

But what about the international rankings that don’t list any German universities in top places? These rankings played no small part in prompting the efforts of the Excellence Initiative: the idea behind it was that a country like Germany must also be internationally visible as a centre of learning. However, if it had really only been a matter of improving Germany’s position in the rankings, it would have been more meaningful to “buy in” several Nobel Prize winners for a short period of time with large sums of money and use them to move up the list, as a number of countries have done, or pay high sums to the producers of impact lists for giving appropriate bibliometric attention to German universities. The fact that policymakers did not do that – irrespective of whether this was an oversight or due to ugnorance of the measuring methods used – has actually benefited research: more substance, less design! If you want to gain a realistic picture of the strength of German universities, you only need to take a closer look at the proportion of researchers at elite institutions all over the world who received their training in Germany: when it comes to centres of learning, Germany is also a strong exporting country.