Land of rocks

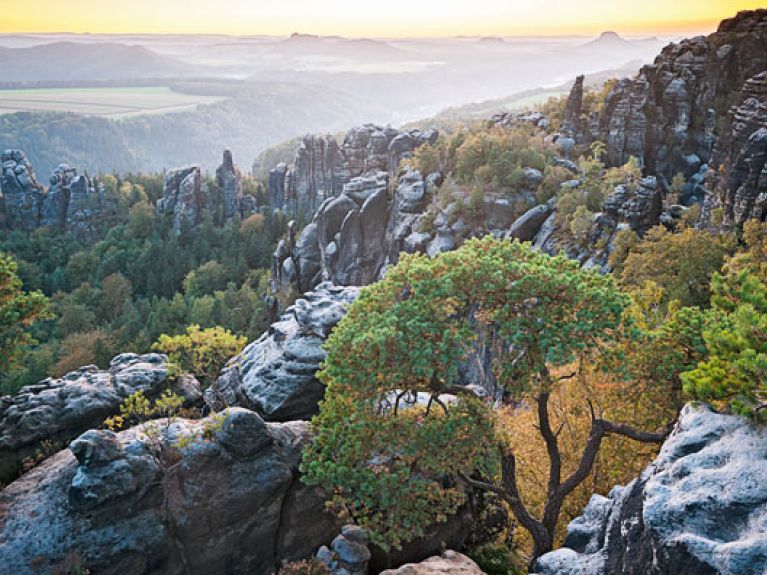

The bizarre, primeval landscape of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains simply overwhelms visitors.

The car ride from Dresden has taken just about half an hour. Then, at an angle to the left of Federal Highway 172, the first table mountain appears. It looks as if its tip has been sawn off. It is a landmark. The road descends into the Elbe Valley, zigzagging downwards. The forest on the steep neighbouring slope comes closer and closer. We’ve reached our destination: Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland or the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, in the extreme east of Germany, near the border of the Czech Republic. Both names are used to denote this particular landscape, yet they reflect quite different kinds of perception. The term Elbe Sandstone Mountains sounds very sober and unwieldy. It invokes images of the huge stone blocks that were once transported the short distance on wooden carts, and nowadays on trucks, to Saxony’s state capital of Dresden, to which they lent great splendour. The term reduces the mountains to their basic element of sandstone. On the other hand, Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland expresses an entirely different concept, an atmospheric sensuousness. This term was allegedly coined by two Swiss landscape painters who discovered many aspects and motifs in the area reminiscent of their home country.

The geological origins of this landscape date far back in time. Millions of years ago, in the Cretaceous period, the area was still under water, and its traces can still be seen today. The subsequent erosion washed away whole sections of rock leaving bizarre shapes. The pillars of rock, sometimes called needles, have shaped the appearance of the region. In the interplay of light and shade, of wind and weather, the shapes constantly transform to create ever changing images in the eyes of the beholders. One guide book calls them “fairy tales in stone”, referring especially to those mysterious places that have given rise to many legends. For instance, the Uttewalder Felsentor or stone gate: they say the devil threw a huge rock at a devout man, but two angels quickly pushed together two walls of rock that caught the stone as it fell. The block is still suspended there, telling the tale of the traveller and the angels. Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland abounds with stories about life, each set in stone.

Nature has been attracting people to Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland for 200 years, since the age of Romanticism. In those days they were students from Dresden’s art academy. They were looking for motifs to paint. Meanwhile, the Painter’s Path has been reconstructed. The 112-kilometre track takes hikers past famous landscape scenes with panels showing Romantic paintings, such as Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. In this way, the observer becomes part of this magnificent work of art.

The journey is its own reward, but it can be quite challenging in places. Walking is the prime means of transportation here. The marked hiking routes in the area total 1,200 kilometres. Especially on the right-hand side of the Elbe, where the Saxon Switzerland National Park crosses the almost unnoticeable border to become Bohemian Switzerland, numerous tracks take hikers through surroundings that closely resemble the ancient primeval forest once again. Meanwhile, large expanses have been surrendered entirely to nature. In other places, there is active human intervention to fell non-native trees. Original forms of animal life have also returned to the region – peregrine falcons and salmon now live here again. Lynxes have been reintroduced, and biologists have even sighted wolves on the outskirts of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains.

Above all, traces have been left by the long history of human settlement. Vast and impregnable, Königstein Fortress stands out high above the Elbe, not far from the Bastei rock formation. They are now huge tourist attractions. The churches are quieter, less dramatic witnesses of 1,000 years of human history. And the deeper you delve, the more there is to experience. Each place has its own programme and its own attractions. There are individual events, such as the Rathen Open Air Stage with theatre performances or the Elbe Sandstone Miniature Park. Train fans can discover several narrow gauge railways operating with steam engines. And the Kirnitzschtal tramway runs along the valley of the Kirnitzsch river. Listing everything would spoil the adventure. But one thing simply has to be mentioned: climbing. The rocks of Saxon Switzerland seem to possess a bewitching attraction for climbers great and small. Children clamber on the lower rocks, to the dismay of their parents, while young people test their skills and nerves at loftier heights.

Some people say that climbing was invented in Saxon Switzerland. Of course that’s not quite right, because climbers find other rocks equally enticing. Even so, about 100 years ago this is where the rules were set up that are still valid for free climbing today: technical aids are allowed for safety purposes only; the actual climbing is done entirely with the hands and feet. Not all of the rock pillars are open to climbers, but 21,000 climbing tracks lead to 1,100 accessible rocky peaks. Nevertheless, despite these countless alternatives, there are occasional tailbacks on some of the tracks.

Saxon-Bohemian Switzerland is comparatively small. Its core area, which is designated as a national park, only embraces around 160 square kilometres, while the entire area of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains covers 700 square kilometres. From Dresden and indeed the whole of Saxony, it’s quick and easy to reach the area – by car, train, boat or bicycle. And once there, everyone can find a place to suit their individual needs. ▪