Help for Syria’s cultural heritage

There are many threats to cultural heritage in Syria. The Federal Foreign Office is engaging with initiatives and networks and thinking about the difficult time after the civil war.

Long lines of people have formed in front of the Pergamon Museum on the Museum Island in Berlin. Men and women are waiting at the entrance with art guidebooks under their arms, and a few families have also put a visit to the museum on their to-do list. They want to see Qasr Mshatta, the caliph’s winter palace, walk through the reconstructed Ishtar Gate of Babylon and take a closer look at the 300-year-old wooden panels of the Aleppo Room. The elaborately painted wooden panels are relics of a time when Aleppo in northern Syria was powerful and prosperous. Today large expanses of the old city centre lie in ruins.

Five years of civil war have wreaked a great deal of destruction in Syria. The war has not spared the country’s six UNESCO World Heritage Sites: parts of Aleppo’s unique covered bazaar burned down during fighting in the area and the minaret of the Great Mosque of Aleppo, which was built in the 11th century, has collapsed. The Syrian Ministry of Antiquities has documented the severe damage that has been done to the famous crusader castle Krak des Chevaliers near Homs, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The pictures show helpers clearing mattresses and waste from collapsed arcades and stone walls full of holes made by shrapnel and artillery shells.

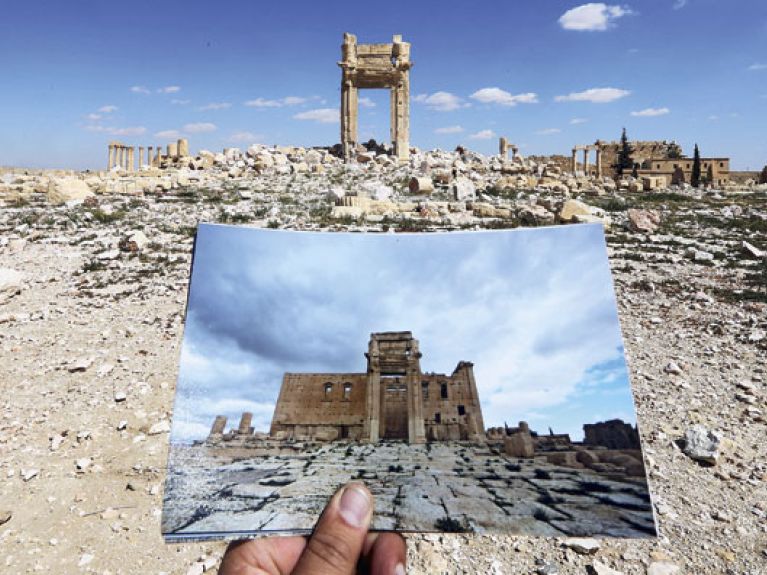

Friederike Fless, President of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), knows that time is running out for cultural heritage: “The dangers are diverse,” she says. They include deliberate acts of destruction by so-called Islamic State in Palmyra, for example, or trench warfare in ancient sites, as well as looting. According to estimates for the year 2015, over 200 out of a total of roughly 740 archaeological sites were damaged by illegal excavations. “The destruction of residential houses and shortages of construction materials are increasingly leading to ancient buildings being pulled down for building material,” says the archaeologist.

Supported by the Federal Foreign Office, her institute and the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin have been working hard since 2013 to compile a digital, web-based register of archaeological sites and historical monuments in Syria. This is because large parts of Syria’s cultural heritage have not been documented by scholars. The researchers have already recorded over 100,000 objects in their system. The Syrian Heritage Archive Project aims to facilitate the reconstruction of ancient sites like Palmyra when the conflict is over.

The destruction in Aleppo, Damascus and Homs will be Syria’s challenges for the future. Germany knows such concerns from its own history: one billion tonnes of bricks and rubble were left piled up in Germany’s towns and cities after the Second World War. No one believed that liveable cities could ever again be created among these ruins. But it was done. “Stunde Null – A Future for the Time after the Crisis” is the name of the first project by a group of experts known as the Archaeological Heritage Network. Under the auspices of the DAI and funded by the Federal Foreign Office, it concentrates initiatives and measures in Syria’s neighbouring countries, as well as planning for reconstruction. “Perhaps we can learn from the Germans how to rebuild a destroyed country,” hopes Bashar Almahfoud, an architect and guide in the Multaka project, which enables refugees to take other refugees on guided tours of museums in Berlin.

Stunde Null carries the hope that Syria will once again become a peaceful, functioning country. “We involve Syrian colleagues who have fled and come to us,” says archaeologist Fless. “They are planning their own future.” These colleagues include Hiba Al-Bassir. She was able to escape from Damascus to Berlin in 2013. “We arrived, were still in a state of complete confusion – and three days later I began my work in the Syrian Heritage Archive Project.” Since then the technical draughtswoman, who completed an apprenticeship as a restorer in Germany, has been categorising the metadata of clay vessels, sections of pillars, oil lamps, “everything that could find its way onto the black market in coming years”.

In June 2016, over 170 archaeologists, architects, urban planners, curators of monuments and other experts assembled in Berlin at the invitation of the Federal Foreign Office and UNESCO to discuss the protection of Syria’s cultural heritage and the danger of art theft. “We are united by our joint engagement, by our concern and the knowledge of the extraordinary universal significance of the millennia-old cultural heritage throughout Syria,” said Minister of State Maria Böhmer. The experts also discussed the question of how – and by whom – cultural sites could one day be rebuilt or reconstructed.

DAI is taking a practical approach to this subject and training artisans in traditional stonemasonry techniques in Baalbek in Lebanon and Umm Qais in Jordan. These projects are being financed by the Federal Foreign Office, while the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) is funding higher education programmes. Syrian refugees can receive scholarships for a joint master’s programme in cultural heritage studies and for the German-Jordanian University in Amman. All the omens point to the future. Hopefully, it will be a future in which interested people will be able not only to see the art treasures of Syria in museums, but also to visit the World Heritage Sites themselves – without long lines of people at the entrances. ■