Preventing oblivion with 152 tapes

To mark the 100th birthday of the film maker and chronicler Claude Lanzmann, the Jewish Museum Berlin is showing an exhibition about the making of his film “Shoah”.

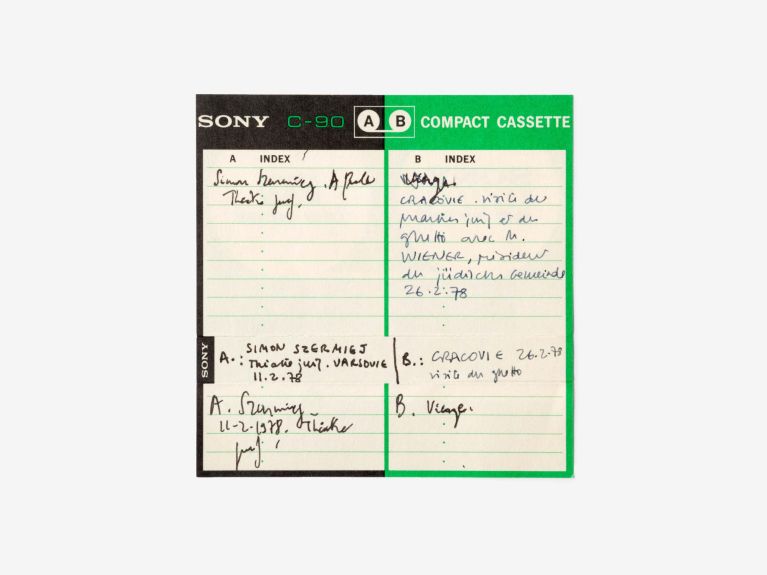

A collection of 152 audio tapes forms the basis of one of the 20th century’s most important documentaries. Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah is considered one of the key testimonies of the Shoah. Both the film itself and the audio recordings it is based on have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage since 2023.

“Shoah” – a story told by contemporary witnesses

There are a number of scenes in Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour film “Shoah” from 1985 that anyone who has seen the film is unlikely to ever forget. The French-Jewish journalist and director was the first to understand that it is impossible to show the extermination of Jews. There is no evidence. The pictures of piles and corpses and freed concentration camp survivors were taken by the Allies after the liberation. This was why Lanzmann refrained from using any archive materials. Instead he brought us the voices of eyewitnesses of the genocide: survivors, perpetrators and witnesses. Mr Lanzmann collected invaluable testimonies from people such as Abraham Bomba, the so-called hairdresser of Treblinka, was forced by the Nazis to cut off the women’s hair at the concentration camp, just before they would be killed in the gas chamber. Many years later, Abraham Bomba was still haunted by this traumatic memory while working as a hairdresser.

The audio archive at the Jewish Museum Berlin

The Jewish Museum Berlin has been showing its exhibition “Claude Lanzmann. The Recordings” since November, and visitors are granted access to Lanzmann’s audio archive for the first time. The archive includes documentation of Claude Lanzmann’s preparations for the film and of how he encouraged the people he spoke to to share their memories. Lanzmann’s widow donated the audio archive to the museum in 2021. Visitors to the exhibition can hear 90 minutes out of the more than 220 hours of audio material, and are encouraged take inspiration from Claude Lanzmann, whose greatest skill was his ability to listen very carefully. “The exhibition offers visitors an extraordinary listening experience. Selected original recordings allow them to join Lanzmann on his research work and to get an insight into the multifaceted memories of the Shoah in the 1970s,” says the historian and curator Tamar Lewinsky.

In the 400 square metres big exhibition space visitors are able to listen to several conversations Mr Lanzmann had while preparing his film. In addition, there are screens showing the transcripts and translations of the recordings from eight languages into English and German. Planning provides for the full archive comprising 152 audio tapes to be gradually published in an online edition by the end of 2027.

Claude Lanzmann: a master of persuasion

“You can learn a lot about Claude Lanzmann’s way of working,” Ms Lewinsky says. Those who commit to listening to the 90 minutes of recorded material will hear how, through years of research work, Mr Lanzmann persuaded both victims and perpetrators to talk to him. His assistant at the time, Irena Steinfeldt-Levy, recalls how his way of asking questions helped those he spoke to to tell their stories, and that not judging anyone had been key. “The people he spoke to were used to shutting themselves off,” Corinna Coulmas adds. She was also an assistant involved in making the film. Claude Lanzmann’s vast knowledge, his precise questions and great patience inspired trust, also in the perpetrators he spoke to. None of them complained after the film premiere, as Mr Lanzmann did not urge anyone to incriminate themselves.

Tangible research work

In a time in which we are flooded with images, the exhibition is an opportunity to listen to Claude Lanzmann’s conversations. The six listening stations enable visitors to track the topics he focussed on and his research work. The conversations Mr Lanzmann had with people who later refused to be filmed are particularly interesting.

Israel’s foreign ministry originally asked Claude Lanzmann to make a film about the Shoah in 1973. He ended up spending twelve years working on the film. Mr Lanzmann believed that the film was extremely important because he was concerned that 20 years later people might deny the Shoah ever happened. The Federal Foreign Office that co-funded the exhibition pursues the same goal. The exhibition is running until 12 April 2026.