The art of remembering

Comics used as teaching materials “Aber ich lebe” (“But I’m alive”) is a graphic novel which preserves the memories of Shoa survivors and offers a new way of approaching history.

How do you describe something for which there are basically no words? How can you capture memories when there will be no-one left to recall them in a few years. The “Aber ich lebe” book project (“But I’m alive”) confronts precisely these difficult and significant questions. It is part of the Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education research project at the University of Victoria in Canada and many other international cooperation partners. Three international comic artists from Germany, Canada and Israel tell three stories of survivors.

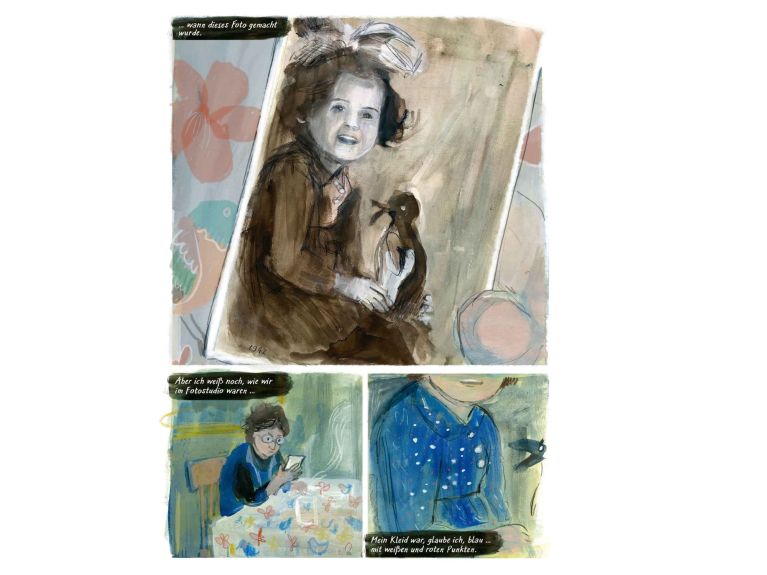

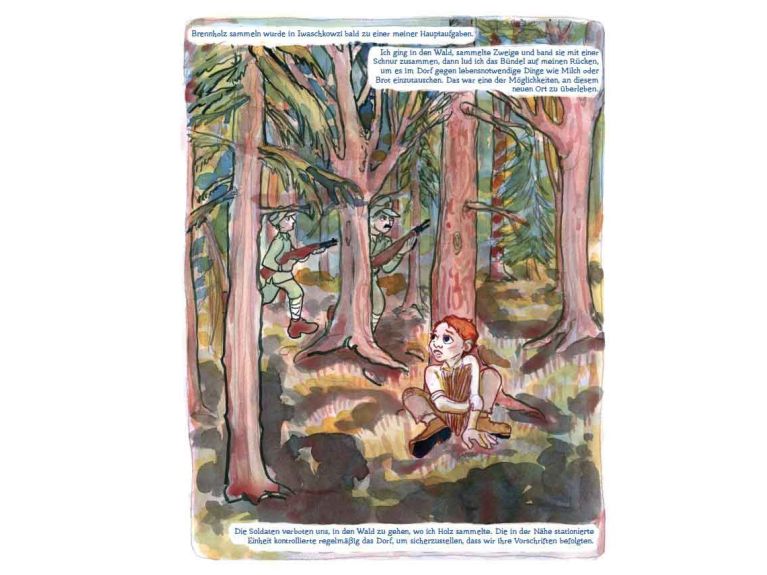

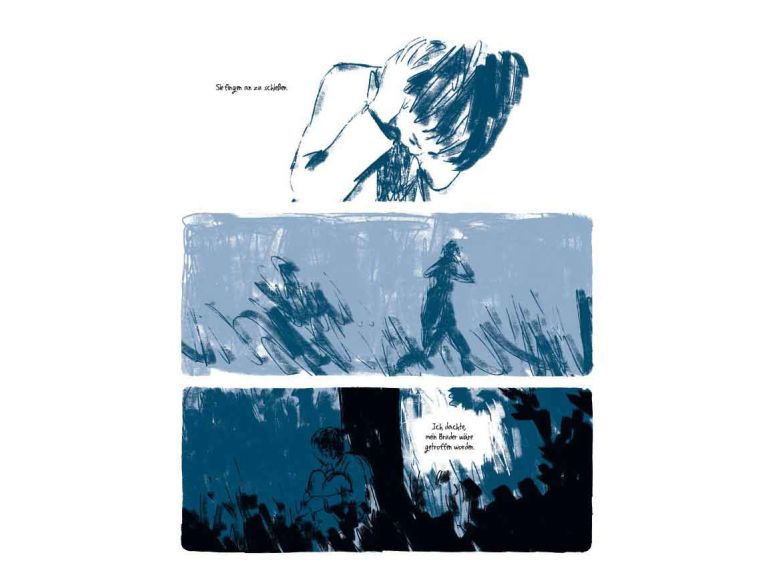

The artists Barbara Yelin, Miriam Libicki and Gilad Seliktar first met survivors of the Shoa in 2019. More conversations followed. Emmie Arbel was a little girl when she survived the Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps. David Schaffer escaped the genocide in Transnistria because he did not follow the rules. The brothers Nico and Rolf Kamp were separated from their parents but members of the Dutch resistance concealed them from Nazi henchmen in 13 different locations. The artists wanted to write down their memories and present them in graphic form so as to preserve them for the future.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent form“We have involved these eyewitnesses at every stage,” says editor Charlotte Schallié when describing the cooperation. “The artists were able to ask biographical questions and we evaluated the sketches together afterwards. The research team did not get involved in the conversations or steer them in any way. On all issues to do with the manuscripts the survivors had the final word.”Schallié explains that the research team were not afraid to make criticisms, but that they still gave the artists a lot of freedom.

They consciously wanted to avoid conducting conventional interviews. “I asked the artists to be involved. Contemporary witness always emerges through dialogue,” she says. The project also triggered many emotions for Schallié as the editor. Her Hungarian grandmother was murdered by the Nazis in Auschwitz. “Empathy, affection, care, concern, connection, sadness – in a project like this, it’s neither possible nor desirable to maintain a distance as a human,” she says. “But the critical and academic distance was never lost.”

A new way of approaching history: comics as teaching materials

“For many people, a comic book might not be their first choice for representing complex memories of the Holocaust, but in the end it was exactly the right format and means of researching the topic,” says Schallié, who explains that things like silence and emptiness can be expressed well in visual form. “Empty spaces in comics aren’t really empty. They create a space for the inexpressible,” she says. “For example, the survivor Emmie Arbel was often not able to remember what she had experienced as a child in the concentration camps. This would be almost impossible to capture in a traditional contemporary witness report, but you can do it in a comic.”

Young people are often taught about the Holocaust from the perspectives of the perpetrators. However, graphic novels like “Aber ich lebe” could be a new way of approaching the topic. “We are in the final phase of editing the teaching materials so they can be published soon. This summer a workshop for teachers from Germany is being held in Yad Vashem where they can learn how to use the book as a modern teaching resource in order to provide a new way of approaching history,” says Schallié.