The flow of European history

Europe’s best ambassadors: rivers that transcend frontiers.

György Konrád, the great Hungarian essayist, once admitted that in Budapest he most enjoyed looking at the Danube. He explained that a yearning to see faraway places also played a role in this. “Maritime nations are always cosmopolitan, but we Bavarians, Austrians, Hungarians and Serbs do not have a sea,” regretted Konrád. “For us, the Danube has the promise of the ocean. On it, we can travel to faraway shores; it runs through us and ends our isolation.”

The river as a window to faraway places. That is the optimistic view of the Danube that Konrád again wishes to venture. Not too long ago, the other, pessimistic view was the sad reality. “The first victim of war is the bridge,” Konrád also realizes. Yet the Balkan war is history, and the Danube now faces the challenges of the future. It should no longer divide, but become part of a new European collaboration. Konrád takes it for granted that a river should be at the centre of this task: “If you look after the river, you look after your neighbours.”

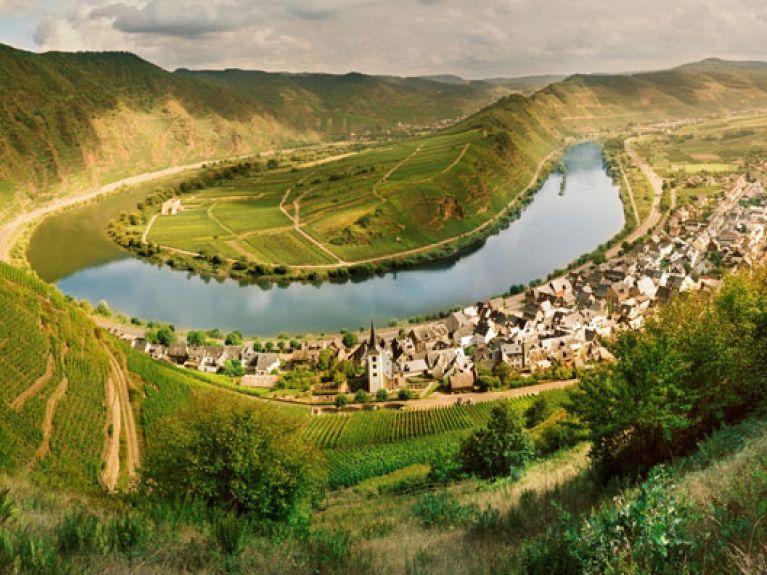

The role that rivers are expected to play today are by no means small. Not only along the Danube, but also along the Rhine, Moselle, Elbe and Oder, they are meant to bring peoples together, to make us forget the frontiers – and the national aspirations – of the past, to connect old cultural landscapes and to stimulate tourism. In confusing times of globalization and hyphenated identities, rivers evidently offer a beginning and an end; if you keep to the riverside paths, you cannot go astray. The routes that we travel are older than we are, since the river cleaved its course through the earth’s surface thousands of years ago. Significantly, rivers also provide that moment of reflection that we otherwise miss so much: we look back upon what was and, full of hope and with a little awe, we look upon what is still to come. River travel is a special experience of time and space.

What a paradigm change. Thirty years have not yet passed since rivers were mainly waterways and drainage gutters. With the industrialization of production also came the industrialization of rivers. New ports emerged and cities and their inhabitants turned away from the riverbanks. Only now and then, when they burst their banks, were people reminded of their rivers. The Rhine became a water superhighway, the Lower Elbe an extension of the North Sea to Hamburg and the Rhine-Main region the home of BASF and Höchst. There was not very much left of the cultural landscapes that rivers had once created.

And suddenly everything changed: deserted industrial areas come back to life as arts centres, riverbank locations become recreation areas and new urban housing developments spring up along the waterfronts. Everywhere cities and their inhabitants are turning back towards their rivers. The rediscovery of river landscapes began in Frankfurt, where the bank of the Main was reinvented as the Museumsufer (Museum Embankment) and transformed into a cultural attraction. In Hamburg a new city district is being created on the Elbe in the Hafencity project, the Medienhafen is paying homage to the Rhine in Dusseldorf, Ulm is moving back closer towards the Danube and promenades are linking the two border towns of Frankfurt and Słubice on the Oder. The new interest in rivers is also creating new images. Riverbanks are no longer dominated by national monuments like the one at the German Corner in Koblenz, but by people enjoying a relaxed stroll. The rediscovery of rivers is also the story of their civilization.

Germany’s cross-border rivers have their own history. Along the Rhine, Oder, Moselle and Danube we approach Germany’s history from without, see it with the eyes of others and enter into dialogue. The same applies to France, Poland and Austria. For that reason, too, the large rivers that transcend frontiers are Europe’s best ambassadors. And, as would especially please György Konrád, the Hungarian and European essayist, they act against the increasing renationalizaton of memories in Europe.