Continuing the shared history

The “Shared History” exhibition at the Leo Baeck Institute New York brings 1,700 years of Jewish history in Germany to life.

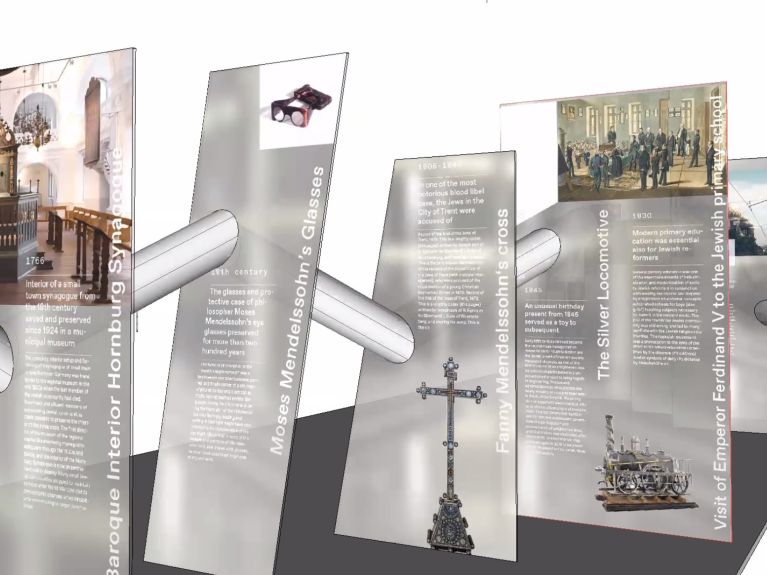

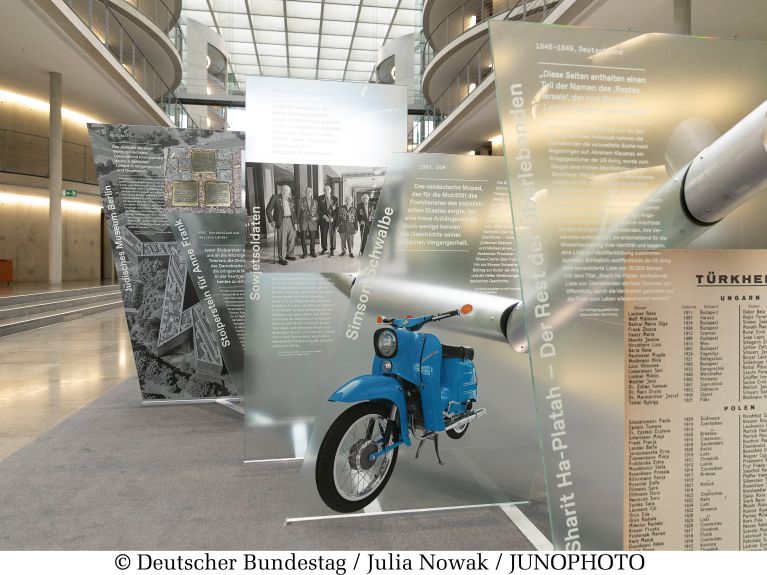

The Menorah Ring, a painting by Gustav Klimt and the “Simson Schwalbe”, a motorcycle manufactured in East Germany, are among the exhibits on show at the Shared History exhibition of the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, which since 2013 has also had a branch at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. 58 objects were selected for the exhibition, with a view to documenting and representing the 1,700-year history of Jewish life in German-speaking lands. Handpicked by historians and museum educators, discovered in archives, museums and libraries and donated by private individuals, the exhibits showcase the shared history of Judaism in Germany.

The exhibition, which not only presents the heyday of Jewish life but also bears witness to Jewish persecution and destruction, can be experienced first and foremost in virtual form: each week, one object will be presented in pictures, texts, films and virtual tours. In the week around 9 November, which marks the anniversary of the Jewish pogroms of the Nazi era, one object from the period of Jewish persecution and the Holocaust will be shown each day.

Opening at the German Bundestag and virtual exhibition

The exhibition will open in the parliamentary building of the German Bundestag on another important historical date: 27 January, the day of liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp, which is now the International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Because of corona, the exhibition will initially be accessible only to the parliamentarians and staff of the German Bundestag.

However, the virtual exhibition also gives people the chance to engage intensively with the shared – or joint – history of German Judaism. The Edict of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great from the year 321 gave Jews in Cologne the right and the duty to become members of the municipal governing body. Though this may sound like equality, it also meant that Jews had to perform more roles and pay more taxes. However, this also proves that they had already achieved a certain standing and wealth by this time.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formDr Miriam Bistrovic, who has run the Berlin branch of the Leo Baeck Institute ever since it was established in 2013, has a number of favourites among the 58 objects. For the oil lamp with Menorah that was discovered in Trier, for example, she contributed a short biography of the Rabbi Adolf Altmann, who found the ring around 100 years ago. This is evidence that Trier already had a Jewish population in the third or fourth century AD.

It is a new, vibrant, diverse, different Jewry that has evolved since then.

It goes without saying that the Holocaust plays a special role in the history of the exhibition. Leo Baeck, a liberal Jewish rabbi and scholar who from 1933 was president of the Reich Representation of German Jews and was later deported to a concentration camp, said in 1945: “The era of Jews in Germany has ended for once and for all.”

Miriam Bistrovic does not see the work done by the institute that bears his name in Berlin as being contradictory: “Did the shared history really continue afterwards?” she asks. And she answers: “It is a new, vibrant, diverse, different Jewry that has evolved since then.” Unfortunately, she adds, it is once again threatened and at risk. The exhibition, however, is not only a sign that the “shared history” must not be forgotten, but also that it can continue.