Ukrainian voices in Germany

Across Germany, German-Ukrainian associations are working to promote understanding between the two countries. Cultural projects are a key focus of their work.

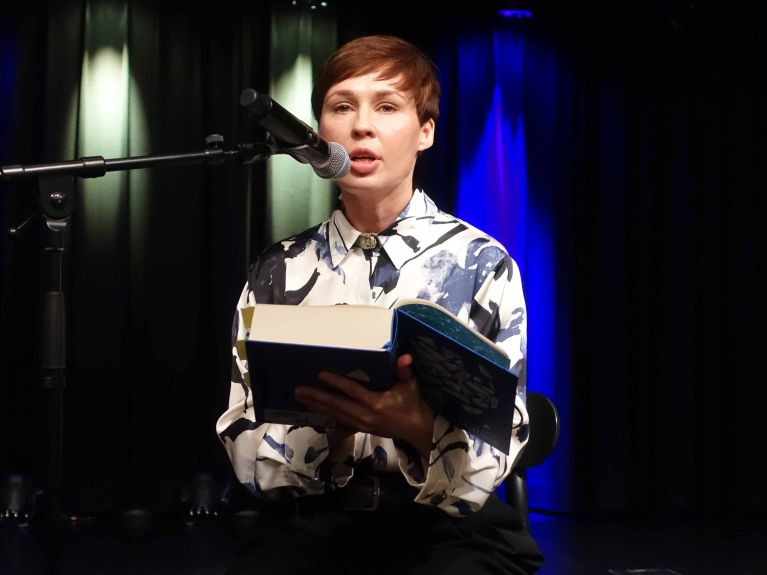

It’s an evening in October 2025 and the Ukrainian writer Sofia Andrukhovych is sitting on a stool in the Culture House in Kehl, a small city in the south-west of Germany. A thick book lies open in her hands. The prizewinning author is reading from her novel “Amadoka”. Her voice is soft and serious. In the novel, the 44-year-old writer interweaves a story of families, love and war with the collective memory of a war-torn country, from the famine under Stalin to Jewish-Ukrainian relations and the Holocaust, up to a soldier who experiences trauma in the war in Donbass in 2014 and returns home with no memory.

Those present described the atmosphere as spellbound. Many Ukrainian refugees attended along with lovers of literature. Andrukhovych speaks in Ukrainian, with live interpretation for the German audience. “The culture of remembrance in Ukraine has become an essential part of life,” she says in the discussion after the reading. “If the enemy denies your language, culture and history, remembrance becomes an act of resistance.”

Foreign Office funding

Andrukhovych was in Kehl at the invitation of the Ortenau German-Ukrainian Association (DUGO), as part of its series of events entitled “Words overcome borders”, which will give a platform to female Ukrainian writers in the period up to mid-December. The association was set up in the spring of 2025. Through its activities, DUGO aims to bring Germany and Ukraine closer together and foster mutual understanding. “Through this series, we want to encourage people to engage with Ukraine,” says Martin Kujawa, the association’s chairperson. “Literature allows us to view the current situation from different perspectives. The authors we have invited are sharing insights into individual and collective experience,” he adds.

Projects such as the readings in Kiel receive funding from the Federal Foreign Office through ifa – Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen. As an institution promoting foreign relations, ifa has been active in Ukraine since the early 1990s, where it targets funding towards members of civil society who campaign for democracy, and the freedoms of art, media and the press. “Against the background of the ongoing war in Ukraine, the role and relevance of these cultural associations has expanded even further,” says Tosin Stifel, head of civil society funding programmes at ifa. “They not only provide concrete assistance for cultural creators who have fled the conflict, but are also increasingly creating space for artistic and intellectual exchange.” Numerous bilateral cultural associations of this kind are now active across Germany in all federal states. In 2025 alone, ifa funded 15 projects.

Promoting Ukrainian language and culture

Eighty kilometres south of Kehl is the university city of Freiburg, which is home to the Freiburg German-Ukrainian Association (DUG Freiburg). In November 2025 the Ukrainian Film Week took place there for the second time, to great success. Demand was such that the organisers had to hire larger halls which could hold up to 300 people.

The programme featured documentaries, children’s films and comedies in Ukrainian, all produced during the war. It included the documentary “Porcelain War”, which accompanied artists on the frontline and was nominated for Best Documentary at the 2025 Oscars. The sci-fi comedy “U Are the Universe” was also screened, telling the story of a truck driver who believes he is the last person in the universe. “I’m so proud that we make films like these in Ukraine,” says Oksana Vyhovska, the chairperson of DUG Freiburg. The films were not just entertaining: they were also met with gratitude. “The audience had tears in their eyes, even during the comedies. For many it was really special to be able to see Ukrainian films in Germany in their original versions,” she explains.

DUG Freiburg was first set up 33 years ago and has around 120 members. Its activities cover a broad spectrum, from helping Ukrainian refugees to find their feet in Germany, to organising concerts, setting up theatre groups and planning exhibitions. The association also set up a Saturday school for Ukrainian children. “Ukrainians are now the second-largest foreign community in Germany,” Vyhovska explains. According to data from the Federal Institute for Population Research, around 1.2 million Ukrainian asylum seekers were living in Germany in 2025. “That’s why the Ukrainian language and culture must be supported in future through more projects,” Vyhovska says.

How memory becomes identity

Back in Kehl, a question to Andrukhovych about her life in her homeland now makes the hall fall silent. Like many other Ukrainian artists, the author still lives with her family in Kyiv, refusing to leave their country despite the danger to their lives. “It has become extremely difficult,” she says. “The attacks are more frequent, the number of drones is growing. Apparently, there were 800 or so in the most recent attack.” In spite of this, she says, hope prevails. Andrukhovych explains how in her novel “Amadoka”, she sought to explain how identity emerges from memory, and how a positive attitude can come about in spite of pain. “We cannot ignore the negative. It is only by acknowledging the difficult moments of history can we draw strength from it.”

ifa – Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen

Since 2023 ifa – Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen has supported bilateral cultural associations with funds from the Federal Foreign Office. Members of civil society who contribute to the foreign policy of associations within Germany are supported through project funding and training and networking opportunities.