Tomato harvest thanks to solar energy

Over 70% of the population of Benin live from agriculture. Renewable energies – introduced with support from Germany – increase the harvest and make work easier.

The air is dry and dusty. The sun here in northern Benin is barely visible behind the clouds. The Harmattan, a northeasterly wind from the Sahara, is blowing. At night the temperatures fall below 20 degrees Celsius. It has not rained for months, and in many places the ground is rock-hard. On the fields of the Alafia Wanru farm in Mareborou, however, one tomato plant stands next to another. Benin’s most popular and most important vegetable is grown here on 30 hectares of leased land. At the end of January, however, not many ripe red fruits are to be seen. It’s not the right time for cultivating tomatoes, which need large quantities of water. Nevertheless, according to Estache W Adje, Technical Director at the farm, “We harvest an average of 1,750 kilos per day.” He nods his head with satisfaction. Some 100 metres away from the 25-year-old manager three women are carrying full buckets to blue weighing scales. Five large woven baskets are already standing there, each weighing 35 kilos. They are ready for transport to the market where there they will currently fetch a price equivalent to between 7.60 and

9 euros each.

Tomato cultivation outside the season is made possible by four solar-powered pumps and an irrigation system. Adje kneels down and shows a black tube with tiny holes. This is how all the plants here are supplied with water. It’s a great development for all those growing tomatoes here – farmers can lease one or several hectares and pay 10 to 20% of the harvest.

Adje, who has worked for the farm since 2018, also remembers very well how arduous and costly cultivation used to be. He indicates a point in the distance: “That’s where the well is.” It is the centrepiece of the farm. Previously, however, a diesel generator was required to pump water. “An employee came very early each morning, turned it on and had to check regularly that everything was working.” The generator had to run for eight hours at a time and swallowed up enormous sums of money for fuel. “Some days we paid over 70,000 CFA francs,” recalls Adje. That is the equivalent of almost 110 euros, more than the monthly income of a cleaner or a day labourer. Of course the farm was constantly dependent on diesel deliveries. That led to further problems because of frequent supply shortages. In a nutshell: “It wasn’t cost-effective at all,” sums up the technical director.

Farming is possible without diesel

The fact that agriculture can be done differently was eventually demonstrated by neighbours who had solar panels installed for their irrigation system on an area of a few hectares. The people at Alafia Wanru saw that the system worked and could also be deployed on a large scale. They made contact with BRCE. Founded in 2002, the firm has its office in Parakou, Benin’s third largest city, which is situated just under seven hours by car from the port metropolis of Cotonou. Many solar companies have their headquarters there. BRCE works in the entire northern part of the country and offers not only the installation of solar energy-powered pumps, but also the sale of complete solar kits.

These small sets include a solar panel, a battery, cables and fittings for several lamps, which can bring electric light to villages that are not connected to the electricity grid. In 2019, according to a World Bank estimate, that was the case for almost 60% of the population – 7.8 of the roughly 13 million inhabitants of Benin. Today, despite all the efforts of the government and international donors, electricity is by no means a given in rural regions.

Fewer electricity outages

The electricity fails frequently in Parakou too, explains Mohamed Amine Sidi, Director of BRCE. “On some days it even happens several times. Appointments then fall through because we’re not there on time, which then annoys our customers.” That was the reason why the company began offering solar systems in 2018. Especially at the beginning, however, more was involved than just installation: “We had to do a lot of persuading. Today, 80% of people understand the significance of renewable energy.” It is especially important that earnings rapidly cover procurement costs and that the pumps, panels and batteries have a long service life.

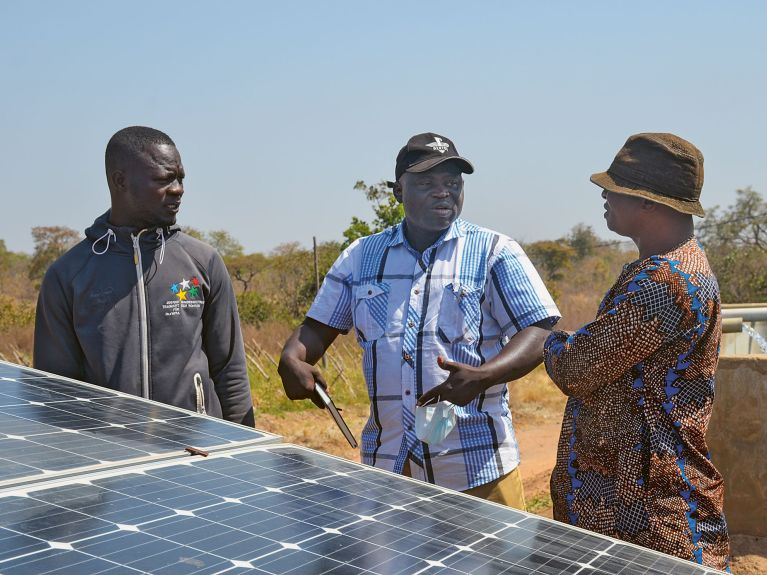

We’re back at the Alafia Wanru farm that Mouhamed Awali Djibril also regularly visits. He is responsible for renewable energy at BRCE and is in close contact with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). The GIZ has been working in Benin since 1978 and currently has over 400 employees there. Its areas of activity include the fields of good governance, the protection of the environment and natural resources as well as training and sustainable growth.

Green People’s Energy is a GIZ project that aims to supply rural regions with local renewable energies. BRCE also receives financial support. In addition, employees have had coaching to draw up business plans and better advise customers about the advantages of solar energy.

Energy 4 Impact, a non-governmental organisation that organises fairs and information events, has been tasked with raising general awareness among the population. In Djibril’s experience it is often the case that people’s acceptance of renewable energies and their willingness to invest increases if they are well-informed and equipment maintenance works. The overall procurement cost for a pump with collector comes to the equivalent of 3,800 to 4,500 euros. If a well needs to be drilled, then an additional 1,500 euros has to be paid. Estache W Adje considers this a good investment that soon pays for itself.

The future lies in agriculture. It can create numerous jobs, especially for young people. I’ve always known I want to work in this sector.

Benin’s present definitely involves agricultural work: one quarter of the gross domestic product is generated on fields and in gardens, where over 70% of people work. The market for fruit and vegetables is steadily growing – especially that for tomatoes. Djibril confirms this: “Tomatoes are the most important ingredient in Beninese cuisine. No dish is complete without them.”

You would like to receive regular information about Germany? Subscribe here: