Born in 1964

We were carefree, well-educated – and there were a lot of us. On baby boomers in post-war Germany.

When I finally arrived, in October 1964, my parents believed the world ought to hear about it and advertised my birth in the local newspaper, the Bochumer Anzeiger. They thought they had done everything right, but they were disappointed because the weekend edition of the newspaper was suddenly full of other newborn boys called Stefan. The Andreas and Bernd wave seemed to have passed; the Ulrich and Dirk wave was still going; and although the Michael wave was reviving, my mother had hoped that her small, localized Stefan reservation would remain protected. But there were no more reservations, we flooded the country. More babies were born in 1964 than in any other year in post-war German history. Almost 1.4 million of us. Month for month a city the size of Siegen came into the world. We were numerous enough to fill all 18 Bundesliga football stadiums to the last seat – and the second division, too. 1964 produced people like Jürgen Klinsmann, Ben Becker, Hape Kerkeling and Linda de Mol. On second thoughts, there are perhaps years with more famous kids.

In 1975, when I went to high school, there were 44 children in my class. Someone was always being sent out to look for more chairs. There were three other students in my class with the same name as me. Being called Stefan had the advantage that your heart didn’t miss a beat every time the physics teacher called out “Stefan!” But it had the disadvantage that you constantly felt people meant you when in fact they were addressing someone else. It was the same for the Dirks, the Ulrichs and the Martinas. We were always being mistaken for someone else, right from the start. None of us was called Marcel-Leonhard or Laura-Chantal. We grew up with big brothers and little sisters, big sisters and little brothers. There were never gifts for just one child under our tinsel-heavy Christmas trees. None of us ever had the feeling of having anything in the world that was exclusively “mine”. But that was our good fortune.

“Where do you all come from, why are you blocking all the interesting jobs?” This is what we are now suddenly being asked by the children of generation crisis, young graduates scraping through from job to job and never finding a secure one. These people gaze at us reproachfully from magazine covers; from everywhere we hear the silent accusation: “Why do you have to take up so much room?” This debate begins every time a young generation starts looking for a career, but these days the tone is becoming more strident. We were crisis children too, but we made fun of the crisis, we drove around it (the crisis) working as part-time taxi drivers. We didn’t take life as seriously, and perhaps we have been rewarded too richly for our ignorance. But I’m getting ahead of myself; I need to tell the story from the beginning.

When I came into the world it was a Saturday afternoon and Bonanza – the series featuring a lovable giant called Hoss – was on TV. Of course, I don’t really know this, but I imagine that the programme was on at that time because it was always on when I was small, as was Daktari and Sportschau, the weekly sports broadcast. It’s important to mention this, because otherwise it would be impossible to explain how we got used to the idea that everything had a happy ending. Of course, later, when our conversations became more political, we were constantly talking about the apocalypse, but we could only do so because, in our heart of hearts, we really believed the opposite: one of our heroes – Che Guevara, Tarzan or Bruce Lee from Enter the Dragon – would ward off the impending catastrophe.

There were a lot of us, and we put up with the lack of space – the claustrophobia of cluttered children’s rooms, the liberating crush of close-dance parties with dimmed lights. None of us found a girlfriend via the Internet. We made our decision without doing a search. We didn’t collate data, we started out without any previous knowledge. We were the opposite of the World Wide Web generation. We led a German life without asking questions. We were close to each other without wanting to be. And when we needed a network, we would ring our friends’ doorbells.

By the time most of us finished high school in 1983 – or in some cases (like me) in 1984 – a worrying phrase was haunting the newspapers. There was a Glut of Graduates: “You’ll all be unemployed,” they said. Every one of us who enrolled at a university to study German, history or some other seemingly useless subject heard this phrase at least once. You’ll all be unemployed. That was what 1964 meant to careers advisers. We heard this sentence, but we didn’t believe it. We were the most cheerful precariat in the world. We drifted from one seminar to the next, relaxed on lawns in front of university buildings, but we didn’t ask ourselves what our next career step would be. The word career itself seemed laughable to us. We lacked any sense of anxiety, perhaps because there were so many of us.

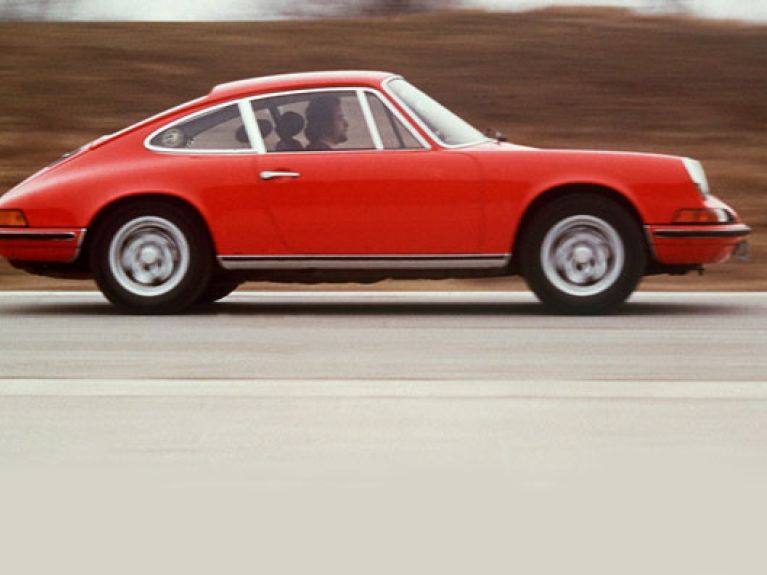

We were the children of the children of the war, the unconcerned sons and daughters of concerned mothers and fathers, and if a generation researcher ever wants to find out something about us, he should take a 1964 map of Germany and mark all the places where people built their first house. This map would be black, the country full of bricklayers’ buckets and roof tiles: this Germany believed in a happy ending. In a damaged country, nothing radiates more optimism than a baby’s cry asserting itself against the grinding of a concrete mixer. We were Germany’s building-site children, the fruits of a careful and ultimately irrepressible confidence. We saw many things for the first time: crispy chicken in the restaurants of the Wienerwald chain, huge ice-cream sundaes in the Italian cafés. We were the kids who sat in the narrow space in the back of a VW beetle when our parents drove across the Alps for the first time in their lives – and reached Italy, the land of longing, where we were allowed to buy ourselves a small bottle of coke with four straws.

A lot of cigarettes were smoked at our parents’ parties at that time; their square packs of Stuyvesant, Lord or HB bore no health warnings. In fact, the 1970s generally got by without package inserts full of side effects. When we passed our school-leaving exams, we could feel our parents’ pride. No one in our family had ever got that far before. “We want you to become something better.” That was our parents’ plea: so respectable, so modest, so simple that it could never become an issue for a conflict of generations.

The 68ers claim they hunted in packs and loved in packs. Yet they don’t even know what a pack is. The 68ers live in a beautiful dream. We are the day after. Our words stem from the 1970s and early 1980s. Our words became bigger and bigger without ever generating any great political threat. Mass university. Mass unemployment. Comprehensive school. Comprehensive university. Whenever a word means masses of something, you can be sure that we have had something to do with it. Our words forced politicians to put up buildings – and not to bring down systems. We were well-behaved and stayed that way. We were a distant rearguard of the street fighters, and only we would have had the ideal troop strength for the fight against systems, but we created nothing symbolic, not even a little Woodstock.

Our Uschi Obermaier was called Suzi Quatro. She made up for her lack of political awareness with her nefarious voice. We listened to her LPs on bulky ghetto blasters like flattened coffins which we insisted on as confirmation presents at the age of 14. That’s why we Protestants felt a bit sorry for Catholics, whose Communion was celebrated at the age of 10 – an age when ghetto blasters were that bit too expensive. Our fantasies of violence ended with the long-haired rockers of bands like Deep Purple, who managed to get their fans to smash up all the chairs during a concert in the otherwise well-mannered Japan. Fortunately, AC/DC were around when Deep Purple broke up. We owe our self-confidence to the optimistic 1970s, the time of our childhood and youth. That’s why we’ve ended up being a little nostalgic. There’s no doubt that the 1970s, the way we experienced them, were a little West German godsend of history.

Actually, there isn’t much to say about us. Nothing amazing to report. We have a birthday from time to time, that’s about it. We’ll be 50 in 2014. A hundred people come to our parties. ▪