“An event that must never be allowed to happen again”

Mariia Ilkiv is researching the fates of victims of Nazi persecution at the Arolsen Archives. Her knowledge of Slavic languages is a big help in her work.

“History was always very important in our family. During the Second World War, my grandfather was interned in a Soviet prison camp for being a member of the political underground movement in Ukraine. Later he talked about this a lot, which is what inspired me to study history. I wanted to acquire some practical experience and find out how my grandfather was able to survive his time in the camp. Because Germany is one of the countries that engages very intensively with its past and attaches considerable weight to historical work, I decided to search for a suitable voluntary project here.

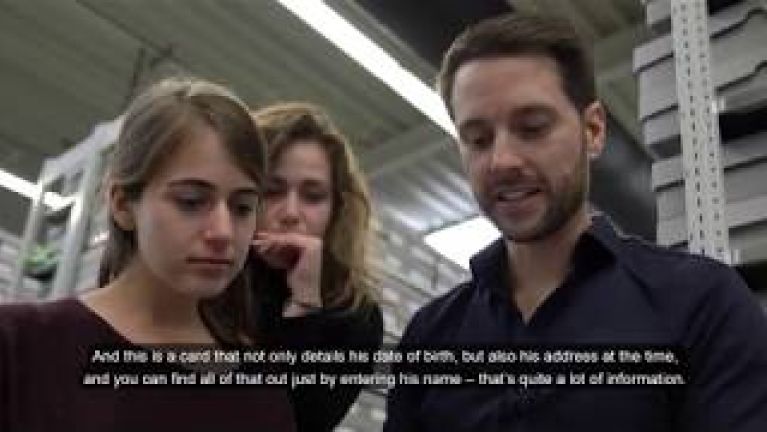

Through the Action Reconciliation Service for Peace, I spent a year doing voluntary service at Arolsen Archives, an international centre on Nazi persecution. I recently began working here on a proper contract. My main task was to respond to enquiries from people from countries of the former Soviet Union who wished to learn something about the fates of their relatives. Some family members had been imprisoned in concentration camps, while others were taken away to do forced labour. Of course, it is difficult for me to handle this information emotionally, but it is a very important job. It not only fulfils me personally; it also makes a crucial difference to other people. In many cases it is members of the second or third generation who want to find out about missing relatives. Some of them had actually survived – but never talked about their experiences.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formBesides countless documents, lots of objects are to be found at the archive; these were sent to Arolsen Archives for preservation after the Second World War. I have described some of these items and have attempted to trace their owners so that they can be returned to them or to their families. Many of the objects belonged to people from the former Soviet Union – photos, letters, watches, a ring, a necklace. The fact that I speak Eastern European languages played an important role in this work, as many notes – for example on the back of photos – were in Cyrillic. From transport lists, registration cards from the concentration camps and numerous other documents from our archive, I tried to find out something about the people who had owned the items.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formIt is nice that Arolsen Archives returns objects to their owners – for in many cases these are the last physical reminders that people have of a relative. In actual fact I only succeeded once this year. It was a pocket watch that had belonged to a man from Eastern Ukraine who probably died at Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg. I began searching for any points of contact, working my way through our research programme. Are any family members still alive? Who can help me trace them? These are the questions that are always asked during the process. The town council in Lysychansk, the home town of the former inmate, helped us a great deal, as did the local history museum there – but we were unable to track down any relatives. Eventually we just had to accept that it was impossible. Then the museum asked whether it might be permitted to exhibit the watch. Just imagine: there is this man who probably died in a concentration camp, but nobody knows what really happened – and decades later this pocket watch finds its way back to the town where he was born. I found this very touching.

Remembering is not a static process. This is very clear to me from the way the Second World War is perceived in my country. When I was still at university, the end of the war on 9 May was always celebrated as a special event. That was the Soviet view of the day. This changed with the 2014 revolution and the new government. Since then we have commemorated this day as a shared catastrophe – an event that must never be allowed to happen again.

Ukraine was already divided during the Second World War – which makes it difficult to have any shared culture of memory. However, this era has not passed; it is not as far away as we think. It is connected directly to us for all time. It is dangerous to believe that the past is a long time ago and will not return. If we do, we risk seeing history repeat itself. It is very important that young people also continue to engage with history. My former fellow students find my work very fascinating. And yet I have often sensed that others fail to understand why I worked here voluntarily, without being paid. But for me it was extremely fortunate to have been given this opportunity at Arolsen Archives.”

Mariia Ilkiv is from Ukraine. After doing voluntary service at Arolsen Archives through the Action Reconciliation Service for Peace, she has been employed there on a proper contract since September 2020.

The Arolsen Archives are an international centre on Nazi persecution and home to the world’s most comprehensive archive on the victims and survivors of National Socialism. Until April 2019, they were known as the “International Tracing Service”. The collection, with information about around 17.5 million people, is part of UNESCO’s Memory of the World.