Democracy in Germany

The Basic Law is the heart of democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany. It was only intended as a temporary measure, but has now lasted since 1949.

Bonn was not meant to be like Weimar, but Berlin was meant to remain like Bonn – what sounds like a convoluted story of cities is nothing less than the chequered history of German democracy, of its failure, its reestablishment and its transformation in the 20th century. The Basic Law, promulgated in Bonn on 23 May 1949, gave birth to the Federal Republic of Germany. It was only to be a “temporary measure”, because soon afterwards, in October of the same year, a second German state, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was founded. This was a result of the Second World War and the collapse of the National Socialist dictatorship. The Basic Law was envisaged as an interim statement of fundamental principles, which is why it was not described as a constitution nor ratified by the people, but approved by the existing states with the exception of Bavaria. The Basic Law was only meant to last until Germany was reunified in unity and freedom.

Parliament and government were strengthened

In 1990, however, when the reunification of east and west became possible, things went differently than expected. Although the government and parliament moved from Bonn to Berlin, the Basic Law survived and became the constitution of the whole of Germany. This was linked with the expectation that the achievements of a stable democracy with the backing of its citizens would continue to endure in reunited Germany. Berlin was meant to remain the way Bonn had become.

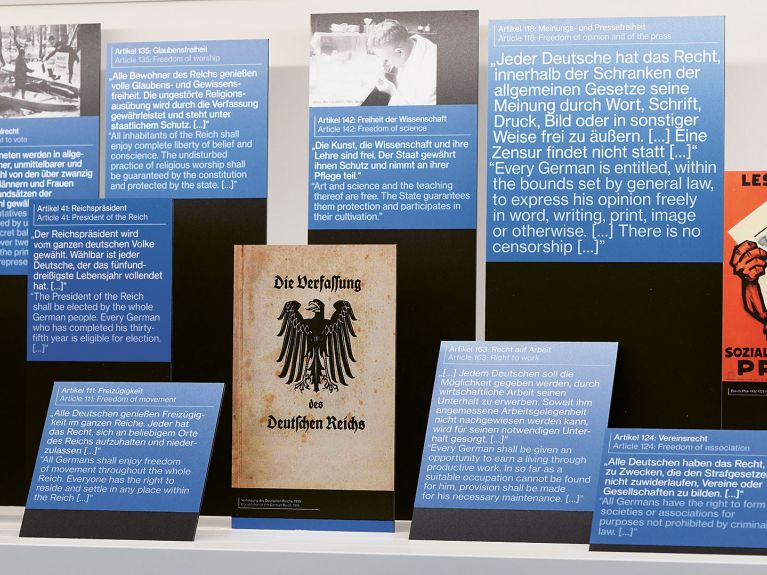

Although the Basic Law claimed validity on the basis of its interim nature, and the loss of national unity was never forgotten, from the very outset it was something more – a blueprint for securing the western state for democracy. The Basic Law aimed to differentiate itself from earlier constitutions and create institutions and safeguards that would prevent a renewed failure of a liberal state, as happened to the Weimar Republic, the first parliamentary democracy in Germany, which lasted from 1918 to 1933. Therefore, the Parliamentary Council, a kind of constituent assembly made up of delegates from state parliaments, attempted to draw conclusions from the failure of the Weimar Republic: it overcame what were considered major structural defects in the Weimar Imperial Constitution, primarily the dual structure of the parliamentary and presidential system. The parliament and the government, the Federal Chancellor, were strengthened, while the powers of the Federal President were essentially limited to representational privileges. The importance of the political parties in the process of shaping public opinion and policy was emphasised; simultaneously, antidemocratic forces, above all unconstitutional parties, could be prohibited. These measures aimed to provide stability for democracy and prevent it again being delivered into the hands of its enemies, as happened to Weimar.

The inviolability of human dignity

The Federal Constitutional Court consequently banned a successor party of the National Socialists and a little later also the Communist Party. This reflected the antitotalitarian consensus of the young Federal Republic – the renunciation of the National Socialism of the past, on the one hand, and dissociation from the second German state, on the other. The latter regarded itself, not least under Soviet influence, as the Communist antithesis of what was described as the “revanchist” Federal Republic. Although the GDR Constitution took on board some principles from the Weimar Constitution, the Socialist Unity Party’s (SED) claim to leadership soon made itself felt when it imposed its will on political opinion-forming and decision-making, did not allow opposition and centralised the political system. As a result, the independence of the states was soon abolished, in 1952. Further amendments to the GDR Constitution followed, strengthening the one-party rule of the SED and the “indissoluble friendship” with the Soviet Union.

The Federal Republic and the GDR stood in strident opposition to one another; they were spearheads in what was known as the “competition between systems”, between democracy and capitalism, on one side, and socialism and communism, on the other. At the same time, the eastern and western states were also able to stabilise themselves because they were located on the frontline of the geopolitical and power political east-west conflict. The GDR was backed by the Soviet Union, and the Federal Republic of Germany received economic and political support from the western allies. As a result, however, the eastern German state was totally dependent on the goodwill and foreign policy of the Soviet Union. It had hardly any freedom of movement with regard to internal policy.

Confrontation with the past

For the Federal Republic, on the other hand, the alignment with the west actively pursued by Konrad Adenauer, the first Federal Chancellor, only had advantages: the economic recovery and integration in the process of European union also decisively favoured the internal process of democratisation and liberalisation that asserted itself mainly in the late 1960s, initially in student protests and then in the new Federal Government led by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) under Willy Brandt. This was accompanied by what could be described as the “self-discovery” of Federal German democracy: a critical confrontation with the National Socialist past and identification with the fundamental principles and values of the Basic Law.

The Basic Law itself was a response to the breakdown of the Weimar Constitution and to the National Socialist dictatorship. As a result, it did not only strengthen the parliamentary system of government by placing the Chancellor in a strong position that could only be shaken by a constructive vote of no-confidence; the 1949 constitution also included a guiding principle that came to shape not only the underlying system of norms, but also the self-image of west German democracy. Article 1 of the Basic Law begins with the sentence: “Human dignity shall be inviolable.” Furthermore, “To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority.” This constituted a deliberate contrast to the inhuman regime of the Nazi dictatorship and represented an innovation in the history of modern constitutions. Never before had this principle been normalised in a constitution; later, others followed: for example, the Constitution of South Africa after the fall of the Apartheid regime. Above all, however, this article became the basis for the rule that fundamental rights apply directly and their spirit must not be infringed by government authorities. This commitment to fundamental rights, the guarantee of legal protection and the legislature’s obligation to the constitution permitted the democracy of the Basic Law to become a constitutional democracy that left no doubt about the primacy of the constitution and the fundamental rights it guaranteed. The establishment of a separate Federal Constitutional Court also proved both exceedingly fortuitous and extremely consequential: constitutional jurisprudence gave the Basic Law its own voice in day-to-day politics and continued to develop it through authoritative interpretation. Furthermore, it provided development aid in the cause of democracy.

“Constitutional patriotism”

This was true in a number of respects. Above all, the judgements of the Federal Constitutional Court were highly significant when it came to the establishment and enforcement of the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of the press and freedom of assembly that are vital for democracies. In the process it was certainly not afraid of conflict with the Federal Government – for example, when Federal Chancellor Adenauer wanted to launch a government television station. The Federal Constitutional Court ruled this incompatible with the fundamental principles of freedom of opinion. On several occasions, it has declared freedom of opinion so “fundamental” to democracy that the economic interests of private parties have had to take second place. This led to the formulation of a new “third-party effect” of fundamental rights that also makes such rights enforceable between citizens and not only between the state and citizens. The Federal Constitutional Court has repeatedly taken the side of citizens. The instrument of the individual constitutional complaint enables citizens to take legal action directly before the Federal Constitutional Court under certain circumstances. Based in Karlsruhe, the court is a long way from Berlin and noticeably removed from the realm of politics. The Federal Constitutional Court has become a champion of the citizen; it has gained “power” as an interpreter of the constitution, as a mediator and referee in political disputes. Polls show that people have a particularly high level of trust in this institution.

Because its rulings have been able to calm disputes during phases of intense party political polarisation, the Federal Constitutional Court has played a major role in making the Basic Law an inclusive constitution that brings society together. This is something that was not envisaged in 1949. Yet over the decades it led to the development of what the political scientist Dolf Sternberger called “constitutional patriotism”, a special form of recognition and appreciation of the Basic Law as the cornerstone of the state. Citizens came to associate the Basic Law with fundamental rights and the achievements of democracy and then considered it so important that they identified with it. In a nutshell, the democracy of the Federal Republic of Germany gained precisely the kind of backing from its citizens that Weimar lacked and which ultimately made it unable to prevent its own destruction.

The GDR, on the other hand, lost the backing of its citizens. By the early 1980s the economic difficulties were already steadily increasing and public infrastructure was in a decrepit state. At the same time, protest was growing stronger and stronger – above all, around the churches, which offered protected spaces. This did nothing, however, to stop the political repression of dissidents, who were arrested or expelled. In the 40th year of the GDR many people attempted to flee to the Federal Republic via Hungary and Prague. Simultaneously, citizens demanded reforms and the freedom to travel – following the example of Gorbachev in the Soviet Union with his policy of glasnost and perestroika. In October 1989, thousands of people assembled for protest marches in Dresden, Leipzig and other cities chanting the slogan “We are the people”. The Berlin Wall fell on 9 November. The revolution on the streets was successful, and the first truly free elections to the GDR People’s Chamber were held on 18 March 1990. However, the path that was to lead to German reunification had already been mapped out. In December the previous year, during the visit of Helmut Kohl, the West German chancellor, banners were displayed that read “We are one people”.

The process of reunification

The reunification of the two German states on 3 October 1990 raised several questions again. Would the Bonn democracy be able to continue and prove successful within the framework of a national-state? The 1992 decision to relocate the capital to Berlin was linked with fears that reunified Germany would become “more eastern”, would put an end to its strong integration in the west and, as a power in a central position in Europe, pursue an unpredictable “seesaw policy” involving power politics between east and west, in the same way, for example, as was once attributed to the German Empire under Bismarck. And finally, what course would inner German unification take, how would the experiences and needs of east Germans be reflected?

Many of the fears were soon overcome. Horror scenarios about Germany’s new potential unreliability faded relatively fast because the path to reunification did not only have to be coordinated with the four Allies, but also remained embedded in the European integration process. Furthermore, France’s fears of Germany as a strong economic (and monetary) power were also eased by the introduction of the euro. The rushed implementation of an economic and currency union between the Federal Republic and the GDR before the unification of the two states accelerated the process that concluded in the Unification Treaty on the Establishment of German Unity. This led to the accession of the states (Länder) on the territory of the GDR, which were also re-established on 3 October 1990, to the territory of the Basic Law. This was linked with a swift transfer of institutions from west to east, a radical change in elites and the attempt to transform a crumbling planned economy into a functioning market economy.

Mood of protest in the east

The speed of this process had its price. Large numbers of people became unemployed because many enterprises from the socialist command economy were no longer profitable. Until today, the Treuhandanstalt, the agency responsible for the economic transformation process, has continued to symbolise mass redundancies and the devaluation of careers – even though it has been possible to create new jobs in the last 30 years and the unemployment rate now almost corresponds to that in west Germany. Nevertheless, a series of structural factors still make many in east Germany today feel they are “second-class citizens”: the strong demographic changes that involved many people moving from east to west, the gap between urbane metropolitan centres and depopulated rural regions with aging populations, as well as lower levels of pay and longer working hours.

Nonetheless, according to polls, people definitely rate their own, personal situations as positive or very positive. At the same time, however, many east Germans say that west Germans do not fully appreciate or recognise their efforts during the past years of continuous change, which have been very hard on them. Politics and the media are frequently said to have a purely western dominated point of view, and their focus on the special situation in the east is either non-existent or inadequate. These and other feelings and findings also explain the mood of protest that has been discernible for some years and is also reflected in voting behaviour in favour of right-wing populist and right-wing extremist parties. Much of this has the character of a belated revolt against the west.

Basic Law is appreciated

This may also be reflected in attitudes towards democracy. As a concept it receives the approval of the vast majority in west Germany and an only slightly smaller one in east Germany. However, scepticism on whether democracy in the Federal Republic of Germany actually functions well is far stronger in the east than in the west. East and west were once much closer together on that question. The societal polarisation and political upheavals that are being seen everywhere in Europe and North America are making themselves especially noticeable in east Germany because the transformation of society and politics has taken place very rapidly and radically here over the last three decades.

It is reassuring to know that the Basic Law is also appreciated in east Germany as a constitution for the whole of Germany – although many of the civil rights activists at the time of the peaceful revolution of 1989/90 deliberated on a new all-German constitution that they wanted to present to citizens for ratification. Nevertheless, in almost 30 years of shared political life people in east Germany have come to accept the Basic Law as much as west Germans came to do so between 1949 and 1989.

Prof Dr Hans Vorländer teaches political theory and the history of ideas at Technische Universität Dresden. He has been Director of the Centre for Constitutional and Democratic Research, which he founded, since 2007.

You would like to receive regular information about Germany? Subscribe here: