On the responsibility of religions for peace

All religions are committed to peace – yet every day there is conflict, war and terror in their name. We hear very little about the peace potential of religions, a competence that politics could make much stronger use of

The successful British author Ian McEwan dreams of a world without religion. According to McEwan, it would be “a world full of humility before the sanctity of life”. Religions, on the other hand, are “at the centre of the great conflicts of our time”, he once wrote in the German weekly Die Zeit. Definitely, agrees Madeleine Albright, former US Secretary of State, in her book The Mighty and the Almighty, in which she says that religions have always been (although not only) a “source of hatred and conflict”, especially in politics. However, she does not wish to abolish religions, but suggests deploying theologians and other religious experts as foreign policy advisers.

Potentials for violence and peace

Intellectuals, politicians, the media, research and, naturally, a majority of people are all spellbound by religions’ potential for violence and conflict. And every day it is delivered directly into our homes by the press, radio and television: holy war, fundamentalist terror, blood and thunder in religious guise all over the world. Without doubt, religion can be a dangerous and destructive weapon in a conflict.

What is not reported in the media is the religious potential for peace. We hear, read and see nothing. Does it perhaps not even exist? And yet the leaders and believers of all religions are committed to peace. Are they only paying lip service? If there is such a potential for peace, however, what does it look like? How does it manifest itself? In good neighbourliness or walking away with a friendly smile? In high-ranking religious representatives affirming mutual tolerance and love of peace? Or does the religious commitment to peace also have political relevance, both concrete and practical, in internal and international conflicts, in wars and civil wars?

Prevention, resistance, mediation, reconciliation

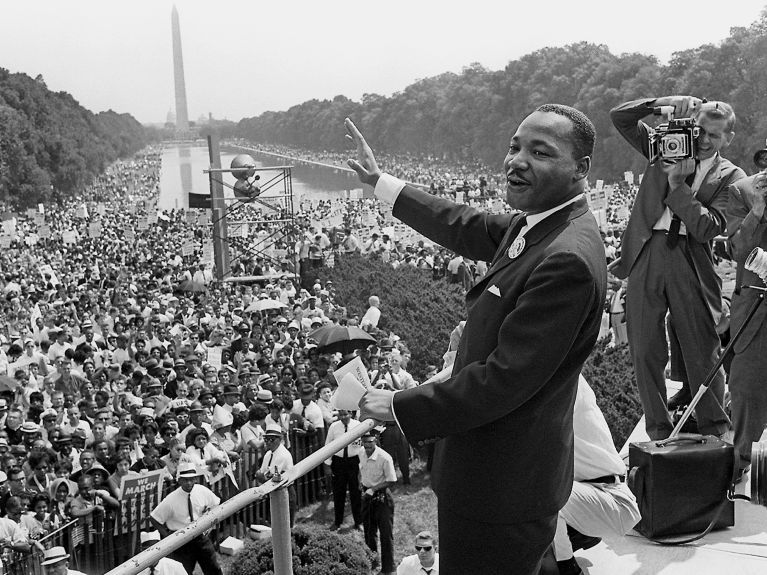

The literature, including the research literature, provides hardly any answers to these questions. Journalism and peace research focus largely on the destructive potential of religion. “If it bleeds, it leads” goes the saying. Hardly anyone has thought to examine the constructive potential of religions. This is all the more surprising because although the most famous heroes of non-violence, global icons of peace – Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King – were political actors, at the same time they were deeply religious figures. And they believed that both – religion and the politics of peace – definitely belonged together. Furthermore, Gandhi and King have countless brothers and sisters: religious actors who have made significant and successful contributions to the de-escalation of conflicts and the prevention of violence.

These examples are just a few of many – ranging from A for Albania to Burma, Kenya, Poland, South Africa and Uganda to Z for Zimbabwe – in which conflicts were limited by the intervention of religion-based actors, conflicts in which religiously motivated men and women prevented or reduced violence, in which they contributed to peace and to reconciliation. Of course, they were not the only actors and rarely were they successful alone. But they made decisive contributions to de-escalation that no one else was capable or willing to make.

If someone wants to aggravate a conflict or wage a war, they do no need religion as the reason.

Peace without religion?

Although it may be true that throughout history people have had to and still face immeasurable suffering and death in the name of religion, it is also equally true that immeasurable comfort has been given, peace made and violence rejected in the name of religion. Would the world really be more peaceful without religion?

Certainly not! After all, if someone wants to aggravate a conflict or wage a war, they do no need religion as the reason. Secular ideologies definitely suffice – for example, nationalism and fascism, ethnicism, imperialism or communism. All these “isms” have a tendency towards exclusivity, to segregation and exclusion. It is then only a small step to confrontation and eventually violent aggression. The vast majority of the millions of war dead during the 20th century were victims of secular ideologies, not of violence based on religion. And now too – contrary to a widespread impression – only a minority of today’s violent conflicts have genuinely religious causes, as for example the Heidelberg Conflict Barometer shows.

Peace through religion!

At the same time there is absolutely no doubt about the fact that many conflicts and wars would have been far bloodier without the influence of religious peace actors. In addition to their commitment to peace and a thoroughly realised responsibility for peace, they stand out because in many cases they have enjoyed more trust from the conflict parties.

As a rule, secular forces – whether politicians or NGOs – face considerable distrust with regard to their true, perhaps hidden interests – above all, when these peace actors come from abroad or are financed from abroad. A religious motivation to make peace, on the other hand, awakens trust on the part of many people.

This trust opens doors and room for negotiation that have often remained closed to secular actors. And yet secular and religious actors should certainly not be considered rivals, but cooperation partners. Both have expertise that can complement one another in exemplary ways. Often, however, religiously motivated (potential) peace actors go unnoticed, their peace competences are marginalised or ignored, and the opportunities for avoiding war or for de-escalation are thus thrown away – to the detriment of thousands of people.

Segregation or understanding?

The additional trust enjoyed by religious actors exists across all religious, cultural and ethnic boundaries, even when conflict parties and mediators belong to different religions. Furthermore, empirical studies show that no religion tends more towards violence (or towards peace) than another. All religions carry the danger of intensifying conflicts – and simultaneously the potential of overcoming conflicts and violence. The wide range of different interpretations of religious writings (or parts of them), customs and traditions in all religions has led to a great number and variety of different denominations, currents, communities and groups. However, this range of interpretations also makes it possible to use religious grounds to justify and legitimise any act – also and especially acts of violence.

When it comes to conflicts, therefore, religions are initially neither good nor bad. They are like the proverbial two sides of the same coin: there is a conflict-aggravating side and a conflict-alleviating, peacemaking side. Which side of the coin is stronger is determined primarily by the responsibility of the faith community and the individual believer. Do they focus above all on the divisive and exclusive aspects of religion, on those parts of the religious tradition that are fearful and show a tendency towards violence – in their own and in another religion – or do they look to religious calls for peace, to a traditional rejection of violence, to commonalities, to shared values?

The religious and cultural environment, religious education or upbringing and religious role models all play a major role here in determining whether one or the other direction is taken. At the same time it is extremely important that faith communities’ responsibility for peace and peace expertise are taken seriously by politics. And it is even more important that religious peace actors are reminded of their responsibility, that they are encouraged and actively involved in peace efforts.

Politics, faith communities and secular peace initiatives have a great deal to give one another and can benefit a great deal from one another. If they were all to contribute their different possibilities and capabilities in joint efforts, then much more peace would be possible than we can imagine today – locally, nationally and globally.