The quiet revolution

How the automation of mental processes is changing the world of work.

Machines have long governed our everyday lives. For thousands of years humans have had the power and knowledge to use the motion of wind and water to make their lives easier and their labour more productive. Better, faster and more powerful machines and tools have multiplied our strength. Since the dawn of the computer age they have also increased our mental powers, enabling us to process information faster and in increasingly different ways and to build systems whose complexity far exceeds the capacity of the human brain.

Each technological advance has influenced and sometimes even very directly determined the structure of society, communal life, communication, work and economic circumstances. Whenever a new wave of technology has come to the fore, there have been sometimes dramatic upheavals. Although these have often caused great suffering, injustice and major shifts in power, they have also led to new prosperity, accelerated everyday processes and previously unknown benefits. Established ways of living, working and thinking sometimes became obsolete within a few years, and skills and knowledge acquired over a lifetime suddenly became worthless. The question of how to overcome the technological upheavals that are currently taking place as a result of digitization, networking, the acceleration of communication and data processing, far-reaching automation and increasingly “intelligent” algorithms is one of the key problems of our time.

When robots become capable of performing activities that are now carried out by assembly line workers in low-wage countries with the same degree of flexibility, there will be a fundamental change in the global economy. Today in many industries there is already a clearly emerging trend towards producing goods near their sales markets. Industries with a high level of automation, such as the automotive sector, have been building new factories directly in their main sales markets for some years now. The lower the proportion of wage costs in the price of a product, the more important other factors become in the choice of production location. Ultimately, transport costs, infrastructure, electricity supply, environmental factors, the availability of highly trained personnel, taxation, political stability and other regulatory factors have a much stronger influence on profitability than labour costs. Capital becomes the decisive means of production because the investments required to enable production with low human input cannot be made without it.

Essentially, this situation exists wherever large amounts of data from and about people are involved. There is significant potential for automation and an increase in efficiency for society as a whole that is not merely related to the eternal drive to sell us more, which is currently the primary focus. The question of how and for whose benefit the data we continuously generate and leave behind should be used will have a very crucial impact on what our future working and living environment looks like.

Currently the treasures of the information age are being privatized without any benefit for the community as a whole – with the exception perhaps of a vague assurance that service will become better as a result. Owning more data about users and customers has largely become an end in itself – driven by the promise that this data will make it possible to realize considerable potential for rationalization and increased efficiency if it is evaluated by appropriately powerful algorithms. However, the process of automation does not stop in the physical world. It is advancing into another domain, which was previously considered genuinely human.

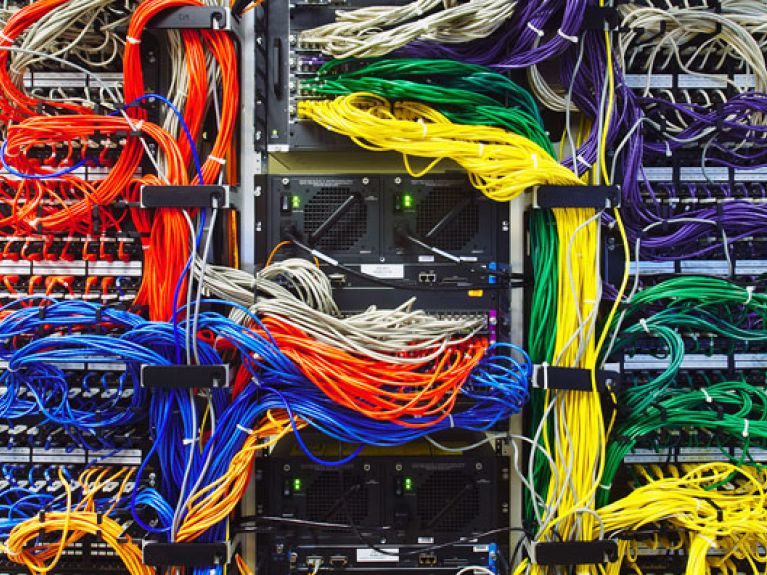

People who think their jobs are safe in the future because they demand cognitive skills that cannot easily be performed by a computer are possibly mistaken. The automation of brain work, the replacement of human mental activity by software and algorithms, has the potential to bring about even greater changes to our working and family lives than those already initiated by robotics and the automation of production. The fascinating thing is that this process is taking place largely unnoticed by society as a whole. A role is certainly played here by the fact that much of this development is difficult to understand and describe and that there are no striking images for the media – unlike the deployment of robots. Who wants to constantly see the same archive photographs of dramatically illuminated keyboards and monitors with ominously moving sequences of zeros and ones? The consequences of the computerization of mental processes are far more subtle than the fact that robots now stand at the places in factories where humans still worked last year.

The automation of physical processes is often not only bound up with a fundamental change in the way in which a business task is carried out. This principle is rather vividly exemplified in the way bank transactions are now carried out. Many bank employees were rationalized away not only because their jobs were performed by robots – after all, that is what ATMs are. Decisions about loans are now no longer taken by humans directly; as a rule, they follow the recommendation of an algorithm that examines hundreds of facts and data points about the customer and his or her financial history. The banker’s gut feeling and experience have been largely replaced by software. On the other hand, we have got used to performing our bank transactions online.

The automation of mental processes functions in exactly the same way in many other areas. Experience, knowledge and intuition are being modelled by software, and statistics, optimization calculations and mathematical probabilities are replacing the often rather fuzzily reasoned and easy to influence decisions of humans. In the long term the combination of the algorithm-friendly reorganization of business procedures and the complete digitization of processes plus software and computing power could even lead to the beneficiaries of the current obsession with optimization and efficiency – namely, business consultants – having to fear for their jobs. If companies can themselves easily carry out analyses that they previously had to obtain from external advisers at great expense, these consultants’ job description is then reduced to the role that is often enough the reason for calling them in: namely, to serve as scapegoats for redundancies.

Many of the new jobs in the highly publicized “digital economy” – in social media consultancies, Internet agencies and Web design studios – have been more about style than substance. The industry is characterized by precarious working conditions, widespread self-exploitation and hanging on from one project to the next, interspersed with periods of dependence on social benefits. Whenever new trends crystallize and quickly become part of our everyday digital lives, there is always a surplus of consultants and service providers who want to profit from the short-term ignorance and lack of understanding of businesses, parties and media.

It would be a big mistake to assume that all this can have no consequences for our society and our personal life. The performance of physical work by robots and machines, the retreat of humans to the roles of designer and manager, and the replacement of many mental processes by algorithms will have profound effects on the structure of our social systems and the power structure of industry and society. The lower the share of human labour – whether physical or mental – in production and value creation, the more the power structure of industry will shift in favour of the owners of capital, the ultimate means of production. If at the same time there are no changes in the basis for financing the state and our social safety nets, the gap between wages and capital income will become even bigger.

It is no longer hopelessly idealistic to wish to stop preserving almost inhumane jobs with more wage cuts and instead have them performed better and faster by machines. A society in which everyone works according to his or her talents and abilities and only as much as his or her life circumstances permit is also no longer a utopia. Our inventiveness and initiative have brought us so far that machines can now perform much of the work we cannot or do not wish to do ourselves.

The question of how the fruits of this development are distributed, whether we succeed in using them for a better, more equitable and livable society, or allow power and money to continue to be concentrated in the hands of a few is one of the central issues of our time. Allowing things to run their course, hoping that the market will resolve the problem, constitutes criminal recklessness that could lead to an abhorrent dystopia. We should seize the opportunity to make the right decisions now and set course for a positive and pro-technology future. That is precisely what differentiates us from autonomous machines, which ultimately do nothing more than follow rules, process instructions and calculate parameters: we should have the insight to put our relationship with them on the right track. ▪

Constanze Kurz is a computer scientist and researcher; Frank Rieger is technical director of a communication security firm. Both are spokespersons of the Chaos Computer Club. The text is based on their book Arbeitsfrei (published by Riemann Verlag).