Where unicorns thrive

The number of start-ups in Germany is growing – including those valued at over one billion US dollars.

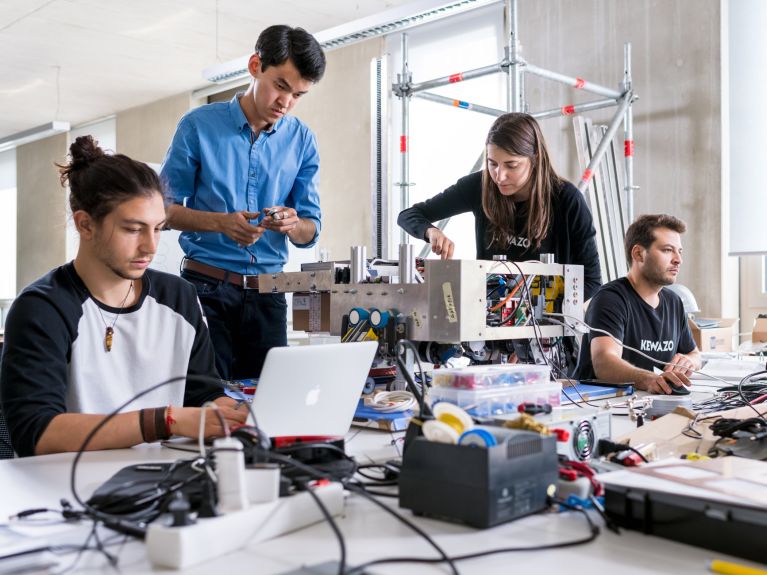

Bringing your own ideas to life and taking off with them – that’s the dream of many entrepreneurs. In Germany, more and more people are ready to work towards making that dream a reality: 2,766 start-ups were founded in 2024 – eleven per cent more than in the previous year. The range of companies is almost limitless and reflects a wave of technological innovation – from AI-supported diagnostics to sustainable mobility, and even smart agricultural technology.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formTake Quantune, for example: this Berlin-based start-up, founded in 2020, has developed a mini spectrometer that can be worn on the wrist. It enables fast, easy, real-time measurement of biomarkers such as glucose, lactate, cholesterol and uric acid. This healthtech company has already received several awards – including the “KfW Award Gründen” from the German development bank KfW. And perhaps most importantly: the start-up has successfully completed its first round of funding.

Berlin for founders: creative, affordable, international

Berlin has long been an epicentre of the German start-up scene. Developers, designers and business professionals from all over the world are drawn to the city on the River Spree. One in three founders has an international background. So what makes the German capital such a magnet? It’s simple: Berlin is a vibrant metropolis, relatively affordable, and it has another major advantage – many of Germany’s venture capital firms are based here.

Just ten years ago, venture capital was hard to come by in Germany. Innovative young companies would often head abroad soon after launching. That’s no longer the case: early-stage funding now works well here. A great deal of private capital is flowing into young companies. And there’s support from the federal government, the federal states and local authorities, too. A state-backed “Future Fund” is providing ten billion euros for start-ups between now and 2030. There are also lots of opportunities to connect investors with start-ups in later stages – and soon at EU level too. “Further developing the European capital market is key to the long-term success of start-ups here,” says Sebastian Pollok of the German start-up association Startup-Verband. “Stock market listings offer a chance not just to strengthen the global competitiveness of our economy, but also to build a self-sustaining financing cycle for start-ups.”

Silicon Saxony on the River Elbe

Change of scene: in Dresden on the Elbe, Bitteiler is attracting attention. A spin-off from the Technical University, the company has developed software that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to compress sensor data. “This means you can use more sensors, capture better data and train more powerful AI models – all without having to upgrade your infrastructure,” explains founder Maroua Taghouti on LinkedIn. Application areas include industrial manufacturing and robotics. Bitteiler has fewer than ten employees – but in April 2025 it appeared at the Hannover Messe, arguably the most prominent showcase for German industry.

It’s also a great example of the ecosystems that have sprung up in other regions of Germany outside the big cities. Nearly 700 start-ups have emerged in Saxony in recent years – including billion-euro “unicorns” like Staffbase and Sunfire, i.e. start-ups valued at over one billion US dollars. Dresden is now known as “Silicon Saxony” – one of Europe’s leading microelectronics clusters. Global players such as Infineon, Bosch and GlobalFoundries work with medium-sized companies and research institutions like TU Dresden, the Fraunhofer and Max Planck Institutes, and the Helmholtz Association. This fuels new business models. Add to that the fact that the cost of living and doing business in Dresden is relatively low – giving founders greater financial flexibility.

Dense networks in Munich

Life is more expensive in Munich, but the popular Bavarian capital has built an efficient, tightly knit and highly successful ecosystem, particularly around the Technical University of Munich (TUM). The Financial Times has just once again ranked the local start-up hub UnternehmerTUM as number one in Europe.

In Munich, founders receive support for building prototypes, pitching to investors, and even coaching on how to navigate the role of CEO. One particular strength is the extensive network linking major corporations such as Airbus and BMW with SMEs, universities, investors and public authorities. Munich offers excellent prospects for tech-based ideas rooted in science or engineering.

The right idea at the right time

Take Helsing, for example: founded in 2021, the company develops AI-based software for military applications. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Helsing drones have been deployed in the conflict. The company secured 450 million euros in funding in 2024. Helsing now employs more than 400 people and is valued at five billion euros.

In just a short time, Helsing has become one of Germany’s billion-euro unicorns. The number of such companies in Germany has more than doubled in recent years – to 28. “The number of unicorns in Germany and Europe has steadily increased in recent years,” says Verena Pausder, Chair of Startup-Verband. “That’s proof of our innovative strength.”

But the dream doesn’t always come true. According to Rafael Laguna de la Vera, there are three key factors that determine the success of a start-up: “The right mindset, a passion for innovation, and a willingness to take risks.” Laguna de la Vera heads the Federal Agency for Disruptive Innovation (SPRIND), which has been identifying, supporting and funding breakthrough innovations since 2019. The agency provides funding quickly, with minimal red tape and a clear focus – 220 million euros in 2024 alone. “We’re entering a whole new era of entrepreneurship,” says Laguna de la Vera confidently.

And unexpected support is coming from the USA: the previously attractive, globally minded US cultural model may lose its appeal due to Donald Trump’s restrictive policies, says the director of SPRIND: “Until now, all the brightest minds wanted to go there – but that’s changing.” The current situation, he believes, is a huge opportunity for even more promising start-ups in Germany and Europe.