Reconstruction amidst ruins

Architect Dima Dayoub is working to preserve cultural heritage in the destroyed historic centre of Aleppo – and to reconstruct entire residential districts.

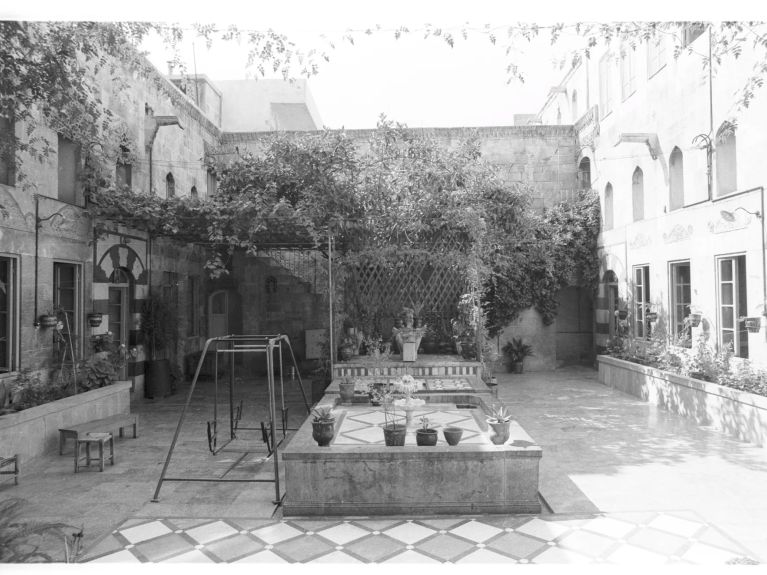

The historic centre of Aleppo is still on this Friday morning. Most people are attending prayers in the mosques and the streets are empty. Piles of stones are packed along the alleyways. Before the war, buildings made of old sandstone with beautiful courtyards stood here. They are a characteristic feature of the historical architecture that was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1986. Lushly planted and with a fountain in the centre, the courtyards help to cool the buildings and are little oases of calm in the bustling city. Now all that often remains of the buildings is only bare walls and glassless window frames. Entire streets have been hollowed out and remnants of mosaics can be found among the stones at the roadside. Yet the sounds of hammers and circular saws are emanating from behind a metal door in the Christian quarter.

This is where Dima Dayoub is working to revive Aleppo’s lost architecture. She is project coordinator for the reconstruction of Beit Wakil and works for the Berlin association “Friends of the Museum of Islamic Art”. The building is the original home of the Aleppo Room, which now belongs to the collection of the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin. It was however severely damaged by the civil war and the earthquake in 2023.

Archive material is helping with reconstruction

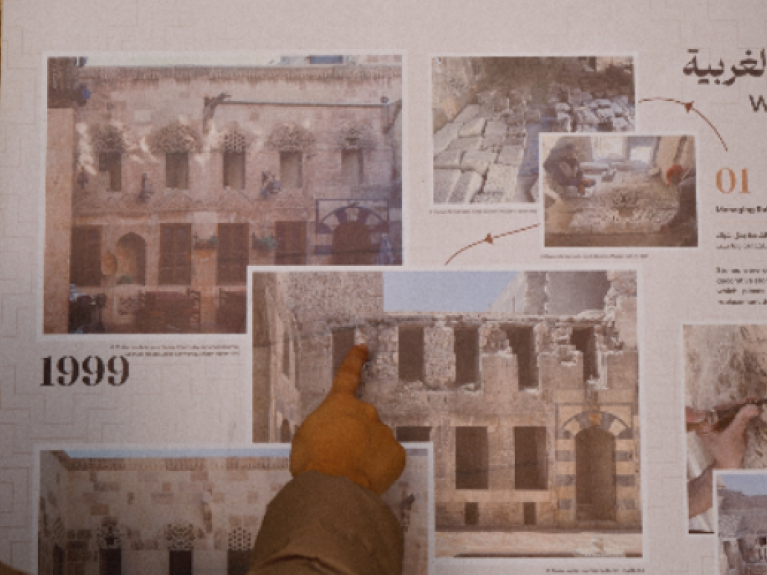

“We’re currently restoring the building and want to preserve the original elements”, explains Dayoub. She is accordingly relying on archive photos of Beit Wakil from the Syrian Heritage Archive Project, which was launched in 2013 at the Museum of Islamic Art in cooperation with the German Archaeological Institute. It was among others financed by the Federal Foreign Office. The project’s objective is to gather and document data in order to preserve Syrian heritage and make it accessible via an open database. “It involves a massive archive that mainly consists of photographs and drawings by researcher and travellers to Syria”, says Dayoub.

The archive comprises some 300,000 documents from the late 19th to the early 21st Centuries, including photographs, plans, texts, videos and documents. “There is a particular focus on Aleppo”, says Dayoub. The archive contains around 50,000 photographs of the city alone. It has also enabled images and plans of Beit Wakil to be preserved. “This material helps us to work very precisely”, explains Dayoub and points to the numerous stone decorations that line the courtyard walls. “We were able to reproduce every detail thanks to the photos. We prepared plans as templates for the skilled workers and apprentices, which enabled them to reconstruct the ornamentation in a manner true to the original.”

Training local skilled workers

“It’s important for us to train young people so that they can perform the restoration work themselves”, says Dayoub. A four-month training course in stone carving attended by seven apprentices and a local trainer therefore began in January 2025. “During this time, we taught them the key techniques for working with historical building materials in a manner appropriate to listed buildings and recreated all the lost stone elements needed for the windows.” This was followed by a further training course in stonemasonry. “We then installed all the pieces they had previously carved”, she explains. Together they thus completely rebuilt the destroyed walls of Beit Wakil. The building’s small windows were originally fitted with stained glass. The appearance of the historical design is however no longer known. “So we intend to conduct our own study to reconstruct the original patterns in the second phase of the project”, says Dayoub.

Her team is simultaneously working on another project supported by the Federal Foreign Office: “We’re systematically documenting all the damage to residential buildings – especially in heavily damaged neighbourhoods”, the architect informs us. Whereas international organisations are mainly concentrating on monuments and public buildings, her team would rather focus on the residential districts. “We’re attempting to bridge this gap and are recording the residential fabric house by house.” This should in the long term result in reconstruction plans in cooperation with the neighbours.