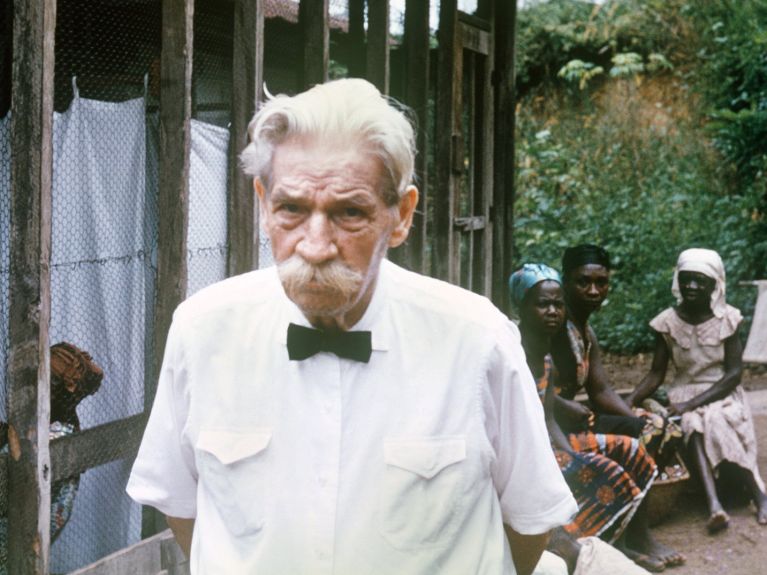

Albert Schweitzer: out of reverence for life

What drove the doctor, humanist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate – and how he built an entire hospital village in what is today Gabon.

During his lifetime, Schweitzer was one of the most famous and revered figures in the world. His reputation grew even further after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952: countless schools and social institutions were named after him, and Time magazine hailed him as the “Greatest Man in the World”.

“The good man”

In the wake of the humanitarian disasters of two world wars, the founder of a hospital in Lambaréné in what is now Gabon was seen as proof that there were still “good people”. Yet his work in Africa was criticised, too. British journalists James Cameron and Gerald McKnight visited him in Lambaréné and condemned what they saw as his paternalistic manner, calling him a “racist” and the “last representative of colonialism”.

Schweitzer defended his approach in the then French colony of Equatorial Africa by saying that it was vital to combine respect for human dignity with a “natural authority”, so as to be respected and enable collaborative action. He summed this up in the phrase: “I am your brother, but your elder brother.”

A multi-talented man with a clear goal

Albert Schweitzer was born on 14 January 1875 in Kaysersberg, Alsace, the son of a Protestant pastor. After attending school, he studied in Strasbourg and Paris, gaining doctorates in theology and philosophy. He was also a gifted organist and an expert on organ building. Several promising career paths lay open to him, but Schweitzer had no desire to become a professor, churchman or musician. When he was still in is early twenties he resolved that after completing his studies he would devote himself to helping those in need.

In 1904 he came across a pamphlet from the Paris Missionary Society, which was recruiting for work in Africa. According to his memoirs, he decided right away that this was the path for him. Outraged by the brutal exploitation of African colonies by European powers such as Belgium and the German Reich, he denounced these supposed “cultured nations” as “robber states” acting as “white masters” and believing themselves entitled to treat people as slaves. For Schweitzer, engaging in humanitarian work in these countries offered a way of making amends for this guilt.

However, the mission society refused to send him as a missionary because they disagreed with his theological views. For this reason, Schweitzer resolved to study medicine so that he could go to Africa as a doctor. His wife, Helene Bresslau, trained as a nurse so that she could accompany him.

The first surgery in a chicken coop

In 1913 the couple arrived at the mission station of Andende near Lambaréné. Their first “surgery” was set up in a former chicken coop. As the days passed, more and more men, women and children came for treatment, and soon they needed larger premises. The outbreak of the First World War abruptly changed everything: as citizens of an enemy nation, the Schweitzers were interned in the French colony and deported to camps in France. They were not able to return to their native Alsace until the war was nearly over. With a daughter now born, their African venture seemed to have come to an end.

Dieses YouTube-Video kann in einem neuen Tab abgespielt werden

YouTube öffnenThird party content

We use YouTube to embed content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details and accept the service to see this content.

Open consent formBut thanks to the Swedish archbishop Nathan Söderblom, who invited Schweitzer to give lectures and organ concerts, he was able to raise the funds needed to plan a return. These lectures also gave him the chance to present his philosophy of culture, based on the notion of “reverence for life”, which he expressed in the phrase: “I am life that wills to live, in the midst of life that wills to live.”

Schweitzer returned to Africa in February 1924. With ever more patients arriving, he resolved to build a new and larger hospital village, remaining in Lambaréné throughout the Second World War. Later he was criticised for failing to speak out publicly against National Socialism. Schweitzer never responded to this charge. Was he protecting family and friends in Germany? Or did he believe his work spoke for itself as the strongest possible rebuke to such an inhuman system?

Opposition to nuclear weapons

Schweitzer did not leave Africa again until 1948, to travel to the United States. In the years that followed he commuted between Africa and Europe, giving concerts and lectures to fund the upkeep of his hospital. As the Cold War intensified, he was urged to comment on the nuclear arms race. Eventually he gave radio addresses warning of the dangers of atomic weapons.

Albert Schweitzer died on 4 September 1965 in Lambaréné, and was buried in the hospital cemetery beside his wife.

In 2024 Alois Prinz published a new biography: Albert Schweitzer. Radikal menschlich