Where antiquity comes alive

Whether it’s a sarcophagus or the goddess Artemis – restorers ensure that millennia-old sculptures are preserved. A visit to their workshop.

There’s a place in Berlin where artistic treasures rest behind closed doors. These special works are cared for by Wolfgang Maßmann, the chief restorer of the Collection of Classical Antiquities at the National Museums in Berlin. Together with his colleague Nina Wegel, he works at the Archaeological Centre, right next to Museum Island. Stone objects from various periods of ancient art are stored here, often sculptures and this is also where the restoration workshop is located.

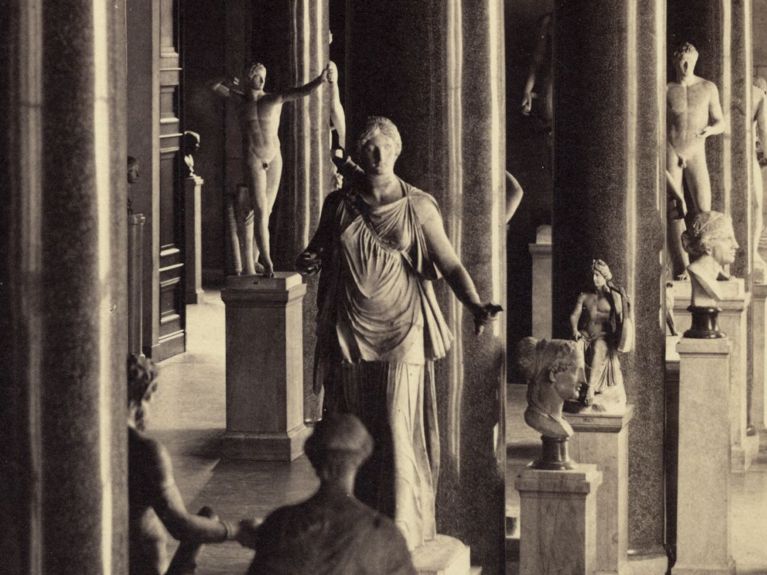

In the middle of the workshop stands an open sarcophagus, like a bathtub made of stone. “That will have to wait until after the exhibition,” Maßmann remarks in passing. He’s on his way to the sculpture study collection. There, marble heads from bygone ages are lined up on three-meter-high shelves. Nameless torsos without limbs lie on pallets, alongside life-size sculptures of ancient deities. Every object is carefully catalogued. But only a small number of pieces are stored here in the Archaeological Centre – the full Collection of Classical Antiquities contains around 27,000 stone objects. Some are on display in the museums; many of them, especially architectural fragments, are kept in an external storage facility.

Restoring a sculpture – the “Artemis Colonna”

In the sculpture study collection, the “Artemis Colonna” – a depiction of the goddess of the hunt – is awaiting her next appearance: it will be on view at the exhibition Founded on Antiquity. Berlin’s First Museum, which runs until May 2026. Afterwards, it is to be incorporated in the permanent collection. The sculpture is among the works first shown on Museum Island nearly 200 years ago. The Royal Museum – today’s Altes Museum – opened with its first public exhibition in 1830. “This little porcelain label is part of the evidence that the “Artemis Colonna” was among the very first items on display,” explains Maßmann, pointing to the base. There sits a small plaque with the number 32, written in elegantly decorative script.

Wolfgang Maßmann and his team have prepared the “Artemis Colonna” for the upcoming exhibition. During a previous restoration a few years ago, missing fingers on the hands were reconstructed in marble. That is something restorers today rarely do any more, Maßmann says. “In the Baroque and Classical periods sculptors frequently added missing parts to statues. Sometimes they even used tools to work the marble in a way that mimicked the rough, weathered surface of antiquity.”

Start by taking a close look

Wolfgang Maßmann still occasionally uses pointed chisels, toothed chisels, and club hammers, too. In the workshop, there’s an entire cabinet full of tools of all kinds. “But before we even begin any hands-on work on an object,” explains restorer Nina Wegel, “we have to understand every detail – all the distinctive, individual characteristics, and any potential issues that might arise.” During an initial inspection, the restorers first check: is the stone structure intact or porous? What is the condition of the adhesive material or the dowels that hold a sculpture together? “Especially with iron dowels, corrosion can cause cracks in the marble and compromise stability. In the worst case, large sections such as arms or folds of drapery can fall off – or the sculpture might even topple over. Preventing that and monitoring it continuously is part of our job,” explains Maßmann.

Some tasks take months to complete

In the stone restoration workshop at the Archaeological Centre, various substances are available for conservation, along with pigments designed to help prevent damage. There’s a shelf with plastic containers filled with powdery materials in various textures and shades: one yellow, labelled “sandstone powder,” others called “coral pink marble” and “champagne chalk”. Tubes of paint, wooden mallets, brushes and binding agents are also ready for use. “For each object we develop a custom plan for its restoration and documentation,” says Wegel. Restorers often spend several weeks or even months working on a single piece. Even after decades in the field, Wolfgang Maßmann still finds this intense engagement deeply rewarding: “Working with these objects is always something truly special – unique – and it simply brings joy.”